In Nepal’s Koshi Province, climate change is worsening floods, droughts, and other threats to smallholder farmers. A new research project, “Documenting Women’s Leadership in Climate Resilience Building in Koshi Province, Nepal,” funded through the Mittal Institute’s inaugural faculty climate research grant program, seeks to capture how women-led organizations are driving grassroots adaptation efforts. Led by Vincenzo Bollettino, Director, Program on Resilient Communities at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; Director, National NGO Program on Humanitarian Leadership and Patrick Vinck, Research Director, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; Associate Professor, Harvard Medical School and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the study uses interviews and focus groups to examine how women’s networks build resilience, the barriers they face, and their influence on local decision-making.

We spoke with Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck about their climate grant, and where they hope their research will lead.

Vincenzo Bollettino; Patrick Vinck

Mittal Institute: Can you both explain how climate change has most affected Nepal’s Koshi Province, and why you chose this area as the focus for this study?

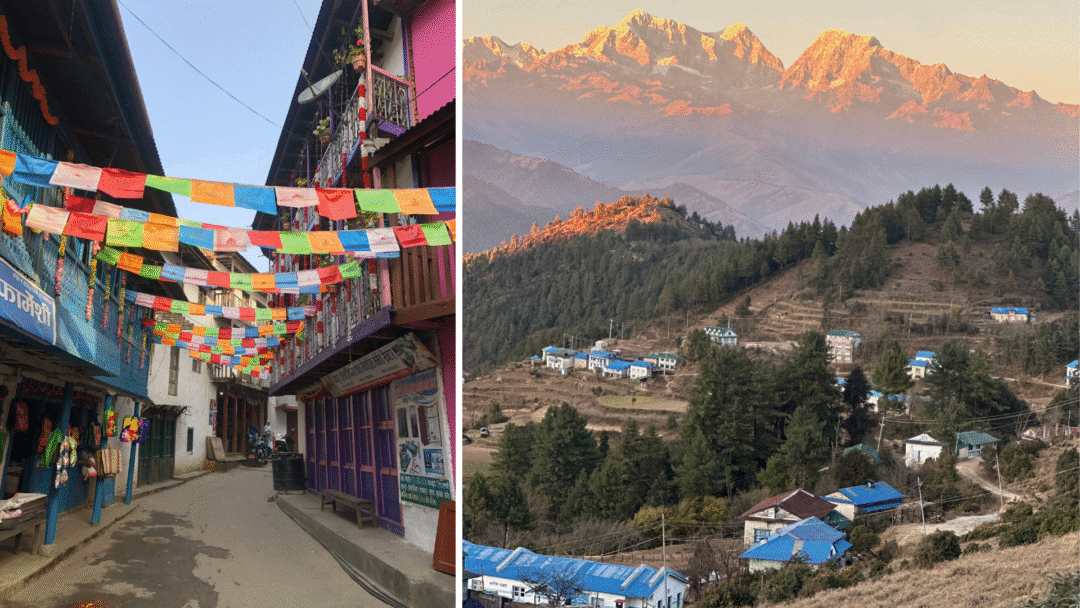

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: Nepal’s Koshi Province is highly vulnerable to climate change. The province stretches from the lowland Terai to the high Himalaya, and experiences a range of diverse climate impacts. Interviews with women’s groups, professional stakeholders and focus group discussions conducted as part of our research project identify climate-related challenges including increased frequency in extreme events such as unpredictable heavy rainfall, recurrent floods (especially in the Koshi basin and Terai), more frequent and severe landslides in the hills and mountains, and rising occurrences of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) in the high Himalaya.

Interviewees noted noticeable changes in seasonal cycles across Koshi. Winters are getting warmer, while extreme heatwaves and intense monsoon rains have become more common. There is untimely or reduced rainfall, affecting both agriculture and water supply. Water sources are drying up impacting household supply, irrigation, and livestock. Agricultural yields have dropped because of erratic rainfall.

There is increased heat stress, soil degradation, and drought. Traditional crops are shifting in altitude or failing altogether, impacting local food security and livelihoods. Climate-induced food insecurity has exacerbated nutritional and other health problems. Dengue and malaria have expanded into hill and mountain areas where they were previously non-existent. Increased use of fertilizers and pesticides (due to changing agriculture) also poses health risks.

Stressors on agricultural production have resulted in loss of livelihoods and have contributed to out-migration among men and youth, frequently leaving women and the elderly in rural areas to manage household survival.

Not surprisingly women are disproportionately affected by climate-related stresses. Their workloads have increased due to the need to fetch water and fuel from greater distances, care for sick family members, and respond to crises.

In short, we selected Koshi Province because of its high level of vulnerability to climate change, its importance as a source of agricultural production for Nepal, its diverse geography ranging from the lowlands to the Himalayas, and its impact on women’s groups and hence the opportunity to explore leadership opportunities for women to positively inform climate-related policy and decision making in the province.

Views of Koshi Province, Nepal.

Mittal Institute: What role have women-led groups played in responding to these climate challenges?

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: Women-led groups, community forest user committees, cooperatives, and self-help groups are often the first to respond at the household and community level during floods, landslides, droughts, and other climate-related disasters. These groups organize responses like food, water, clothes, and sanitary materials distribution to vulnerable households after disasters.

Women-led groups coordinate logistics for evacuations and provide protection for children, pregnant women, and elderly. These groups also support disaster preparedness measures by creating savings funds for emergencies. They also play an important role in climate adaptation work, including collective kitchen gardening, afforestation, and water source rehabilitation including planting trees at water points or along riverbanks to reduce erosion and maintain water access.

Several groups lead awareness campaigns to reduce use of plastics, promote organic fertilizer making, and educate on sustainable farming practices. Others have supported the switch to alternative livelihoods like beekeeping.

Despite the diverse ways these women-led groups are promoting climate adaptation measures and improved preparedness for climate-related disasters, they face significant constraints. They often face challenges of being included in decision-making in only tokenistic ways and are impeded by deep patriarchal norms.

Despite the diverse ways these women-led groups are promoting climate adaptation measures and improved preparedness for climate-related disasters, they face significant constraints. They often face challenges of being included in decision-making in only tokenistic ways and are impeded by deep patriarchal norms. Several interviewees suggested that in official decision-making, their participation is used as box-ticking rather than for meaningful influence. Women’s groups also face barriers such as lack of financial independence, limited access to technical training and resources, and inconsistent project funding. Successfully scaling networks of women’s groups across the province has also proved challenging.

Yet, women’s groups are increasingly pushing their way into local-level disaster risk, climate adaptation planning. In some municipalities, women’s groups have directly lobbied for and implemented climate-adaptive initiatives such as improved irrigation, and afforestation drives. Several of these groups advocate for women’s rights and perspectives within disaster committees and planning forums.

Women’s groups are increasingly pushing their way into local-level disaster risk, climate adaptation planning. In some municipalities, women’s groups have directly lobbied for and implemented climate-adaptive initiatives such as improved irrigation, and afforestation drives.

Women-led groups play an important role as educators for climate and disaster awareness. They host peer-level training and meetings to discuss environmental changes and share adaptation practices. Several other groups have created group savings and business cooperatives designed to building a financial safety net for local families.

Mittal Institute: Can you share a glimpse of what you’re learning so far, especially about the barriers women face or the ways they’re shaping local climate resilience?

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: This response is still preliminary as we are just now in the process of coding and analyzing the data. I will frame this as both some of the barriers that are emerging in the data and ways in which women’s groups are leading to overcome these barriers.

Women report that climate change is having a direct impact on communities that experience disasters like floods, landslides, and wildfires, as well as more gradual changes such as an increase in pests and loss of crops. This has a disproportionate impact on women who are primarily responsible for water and firewood collection, household chores, caring for children and elders, and local food production. As mentioned earlier this vulnerability is exacerbated by out-migration of men, leaving women to manage farms, families, and navigate climate-related crises.

Women’s participation in the public domain, including attending climate trainings, meetings, and cooperative activities, is systematically constrained by their domestic responsibilities and social norms. Meeting times, and lack of support at home serve as barriers. Strong patriarchal and caste-based attitudes also restrict women’s mobility, autonomy, and confidence. This was clearly reflected by both women and men, and across rural and urban areas. Women are sometimes mocked for attending training, discouraged from taking leadership positions.

Sadly, some women suggested that in addition to male resistance, women themselves sometimes hinder others’ progress through jealousy, and competition for limited opportunities.

Even in cases where laws mandate women’s representation in committees, actual leadership, and decision-making power often remains with men or better-connected women. Women also have limited access to information about opportunities. Lack of control over financial resources, and underappreciation of women’s experience and knowledge, are additional barriers.

Despite these challenges women are increasingly emerging as leaders in local climate response, often innovating with little support. Women’s groups are actively working to protect water sources through pond restoration, and protection of water sources. Women’s groups are engaged in forest conservation. In fact, many forests in Koshi are managed entirely or primarily by women’s committees.

In some municipalities, women’s groups successfully lobbied for construction projects to protect water resources, and others have produced eco-friendly alternatives to the use of plastics including the development of tapari-leaf plates. Several women were engaged in climate activism, climate education campaigns, radio programs, and grassroots awareness-raising.

Focus group discussions with women’s groups in Koshi Province.

Mittal Institute: Ultimately you hope to translate your research findings into actionable climate leadership training sessions for women community leaders. Can you elaborate on how you plan to do this, and how will you share it with local leaders?

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: We intend to work closely with a Nepal-based women-led NGO that serves as a donor to women’s initiatives throughout the country.

We are analyzing all the focus group, key stakeholder interviews, and women’s groups interviews and will be working with the donor NGO to translate these findings into policy recommendations and training for women’s organizations.

We will share the focus group notes and KII narratives (stories of climate impacts, barriers, successful initiatives) from the local context and work with the NGO to develop relevant training that supports capacity building for women’s organizations especially on climate adaptation measures though the training will be broadly relevant in advancing women’s groups engagement in decision making and policy formulation.

The Program Lead in Nepal, Dr. Ganesh Dhungana.

Tentatively, this training would cover things like understanding the local impact of climate change, skills for effective women’s leadership both formal and informal, mapping barriers to participation, communication and negotiation, team building, project planning, and advocacy, and climate adaptation solutions in practice – drawing on already successful initiatives (like pond restoration) and sharing these lessons and approaches widely.

We also hope to discuss and support networking women’s groups so that they can work together to amplify women’s participation in climate adaptation action, policy making and decision making. This might look something like establishing women’s networks in each ward to support ongoing learning, connecting women’s groups with already successful women leaders, and using successful leadership stories to inspire other women.

We believe that to be successful, the trainings will have to tackle both structural and social barriers, and the content will need to address the lived experience of women already leading climate adaptation in Koshi Province. Leadership and unity of purpose will be critical to program success in addition to practical skills.

These conclusions and recommendations are expected to evolve as we analyze the data and co-create forward solutions with women’s groups through feedback and discussion.

Women-led interviews with women’s group participants.

Mittal Institute: What do you see as the most pressing obstacles to supporting grassroots women-led climate initiatives?

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: We elaborated on some of the barriers to women’s participation in decision making on climate adaptation and policy making. These obstacles are structural in the form of having limited control over financial resources, limited access to training and education, and tokenized participation in forums. There are also significant cultural and social norms that make it difficult for women to actively engage in climate policy and action.

Women’s time and energy are dominated by unpaid care work, and household chores. This leaves little time for attending meetings, trainings, or leadership roles in climate initiatives. Many women say participation is only possible once all home duties are complete, so they miss events, or attend without full engagement.

Households and communities often question, mock, or restrict women who try to engage in community activities, especially leadership positions.

Women’s groups also struggle to access funding at the local level, with access often tied to politics and connections. Even when supported by donors, support is often short-term and not sustained. Women’s groups also have limited access to training opportunities in climate adaptation skills, proposal writing, and have limited technical climate knowledge.

Local governments and NGOs sometimes bypass women’s groups or engage them in supporting roles, but do not necessarily trust them with leadership, or decision making.

Collective action by women’s groups is sometimes impeded by caste and class divisions. Inter-generational or peer jealousy is also a barrier. In one focus group discussion women stated:

“Another issue is the lack of unity among women. Sometimes, women themselves hinder each other’s progress. If one woman moves forward, she should uplift others, but jealousy and insecurity often get in the way. Older women should support younger women, but it is not happening in our community as we lack such mentality. But, we should be thankful that we are receiving support male community members. sometimes, they motivate us to work, but you know we all have to finish all our household chores, which still bind us.”

Mittal Institute: How can lessons from Koshi Province inform climate adaptation strategies across South Asia?

Dr. Bollettino and Dr. Vinck: We hesitate to draw conclusions for South Asia broadly given the diversity of country and community histories, languages, cultures, social norms, etc… However, some lessons are likely relevant in countries across the region.

The experience of women’s groups in Koshi Province demonstrates that climate impacts and adaptation are gendered, with women facing greater hardship but also involved in local resilience. We expect this is generally true across South Asia where patriarchal norms, and things like unpaid care responsibilities are common.

The experience of women’s groups in Koshi Province demonstrates that climate impacts and adaptation are gendered, with women facing greater hardship but also involved in local resilience. We expect this is generally true across South Asia where patriarchal norms, and things like unpaid care responsibilities are common.

We believe that across the region, women-led local organizations and groups have significant and under leveraged abilities. Climate adaptation strategies need to tackle not just technical issues, but social and institutional exclusion. Women’s groups, indigenous groups, across the region have strong experiential and local knowledge, but their know-how is often informal and underutilized. Across the region, many climate adaptation funds target external NGOs/consultants, despite rural women being on the frontlines. Even where countries have strong climate policies and frameworks, power is rarely devolved to the local level. Fragmentation of climate adaptation and limited effective networking among local organizations is likely something that is true for Southeast Asia broadly. There is room for improved network building among groups domestically and across countries in the region. A good deal of climate adaptation is embedded in routine local management of resources, farming, and other social activities. These activities need to be understood by national-level policymakers and decision makers.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its Steering Committee.