The State of Architecture in South Asia series opens its fall lineup with a September 25 talk exploring the costs of ‘free housing’ in Mumbai. Sai Balakrishnan, Associate Professor of City and Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, will examine the Adani Group’s acquisition of the contract to redevelop Dharavi, often described as “Asia’s largest slum,” and the most coveted asset in the redevelopment: air. She will be joined in conversation by Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization, Harvard Graduate School of Design. We spoke with Prof. Balakrishnan to learn more about her research and what we can expect in her talk.

Mittal Institute: Prof. Balakrishnan, what are “air rights,” and how are they being used as incentives in the Dharavi redevelopment project?

Sai Balakrishnan: Many would argue that land-use planning is the bread-and-butter of what urban planners and municipalities do. In the vertical cities of Mumbai, New York, and São Paulo, however, the real estate game is no longer just about land in the traditional sense—it is about the air above it. Mundane land-use instruments like the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) and Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) enable air to be regulated and valued as a form of property that is distinct from terra firma land. Land-use planning, then, entails the ownership, regulation and valuation of distinct forms of vertical property: the land (terra firma), the air rights above it, and the subterranean resources (such as groundwater and coal) beneath it.

Prof. Sai Balakrishnan, left, conducts fieldwork in Mumbai | By Aslam Saiyad.

Since the 1980s, local governments worldwide have faced severe fiscal austerity. In response, many have turned to entrepreneurial strategies for raising revenue, with air rights emerging as a particularly attractive tool. In Mumbai, for example, local and subnational governments incentivize developers by granting them additional air rights. In return, developers must construct “free housing” for slum dwellers. At first glance, this fiscal–social contract appears to be a win-win: subnational governments can leverage zoning powers to, quite literally, generate revenue out of thin air, while slum dwellers receive ‘free’ housing. Politically, the arrangement is expedient—unlike taxation, which carries redistributive implications that are often electorally contentious, or debt, which carries long-term liabilities, air-rights incentives allow governments to meet their social obligation of housing through a turn to ‘free’ air. In a city where land prices rival those of Midtown Manhattan, developers are eager to capitalize, and slum dwellers benefit from promised ‘free’ housing.

My research (and talk) focuses on this ‘free housing’ policy. The ‘free housing’ policy signals a new social contract of distribution without redistribution, with political appeal to the municipality and developers. And yet, here is the puzzle. Mumbai’s air-rights market initially failed to take off. Despite having the strong backing of all political parties, there were hardly any takers for air-rights. It took mundane but immense planning work—including the reinvention of a humble parastatal—for the air-rights market to take off and get stabilized.

In short, my research critically unpacks the fiction of ‘free housing’ and ‘minting revenues out of thin air.’ It reveals the costs and contradictions of ‘free housing’ and the new spatial inequalities generated by the air-rights market.

Mittal Institute: What does the Adani Group’s involvement signal about the role of private corporations in urban planning and public housing?

Sai Balakrishnan: The redevelopment of Dharavi—and other so-called “slums” in Mumbai—reflects a broader trend in contemporary India: the privatization of essential public resources. In Dharavi’s case, municipal lands are being transferred to private corporations under the guise of providing “free housing.” By granting developers air-rights as incentives for constructing such housing, the subnational state seems to be minting revenues out of ‘thin air.’

But this raises fundamental questions: Who owns the air above a plot of land? Who should own it? These normative conflicts between the public and the private have long been at the core of land-use planning. The Adani-led redevelopment of Dharavi intensifies these debates, extending them into a new frontier—the domain of air.

In short, the air-rights market rehearses old planning questions in a new context: what do we mean by ‘land’ in land-use planning? As planners and planning institutions enable the severing and stacking of air-rights into new forms of enclosure, how should we reconceptualize land-use planning to reclaim the public city?

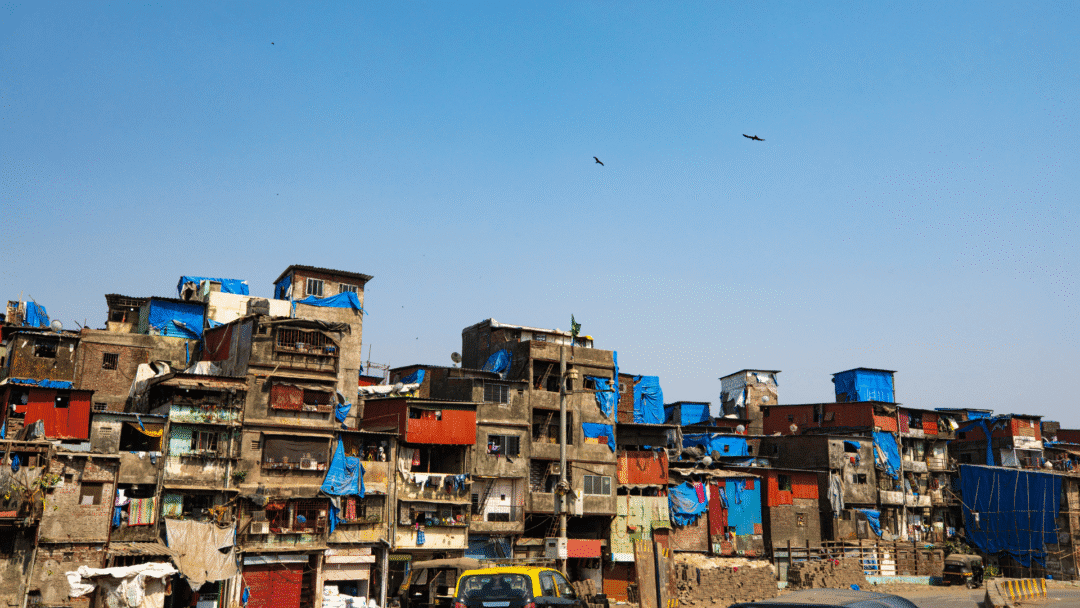

Aerial view of Dharavi slum in Mumbai | Tayiba Photography

Landscape view of Dharavi, Asia’s biggest slum | By Gemini

Mittal Institute: What role has the state historically played in the redevelopment of settlements like Dharavi?

Sai Balakrishnan: Mumbai has long carried the unfortunate moniker of “Slumbai,” and what we are witnessing today is the latest attempt to render the city “slum-free.” Dharavi is the most recognizable ‘slum’ in Mumbai, and it is now at the center of this ‘slumfree’ policy. Just north of Dharavi lies the Mumbai international airport, also promoted by Adani. Pressed against its boundary walls are the sprawling Kurla ‘slums,’ whose cerulean-blue tarpaulin roofs are visible to anyone flying into the city. These slums loop northward into the neighborhoods of Ghatkopar, Chandivili, and Powai.

This geography matters for several reasons. First, the ‘slums’ of Kurla, Ghatkopar, Chandivili, and Powai are far larger than Dharavi, and any discussion of Dharavi’s redevelopment must be contextualized within this wider landscape. Second, the Kurla-Ghatkopar-Chandivili slums stretch along the Lal Bahadur Shastri (LBS) Marg. During the peak of the Cold War in the 1960s and 1970s, LBS Marg was the thriving industrial spine of Mumbai. It is no accident that the largest swathe of so-called slums emerged along the LBS Marg. My research looks at archives from business associations in the 1960s and 1970s, and I find that the planners during this period actively encouraged small-scale and home-based workshops to develop as ancillaries to the large factories. These ‘slums,’ then, did not develop outside the master plan, but they were intrinsic to the state-led developmental strategy of ancillarization. In short, it is a category mistake to view ‘slums’ as a housing problem; they are more aptly characterized as localized agglomeration economies.

It is a category mistake to view ‘slums’ as a housing problem; they are more aptly characterized as localized agglomeration economies

Out of this historical conjuncture emerged a new constituency: electorally organized yet economically unorganized resident-workers. The collective struggle for land occupation enabled access to low-rent land, which in turn enabled home-based and small-scale workshops to get unevenly articulated into global supply chains. It was also during this period that the Shiv Sena exploded onto Mumbai’s political map as a (then) nativist party.

Recuperating this Cold War history of slums is crucial. With only a few exceptions, this period of ancillarization remains shrouded in a black box. While there exists a rich body of scholarship on slums in the late colonial era and again in the post-liberalization period (after 1991), the planning history of slums between the 1950s and 1980s has been largely neglected. Rewriting this missing chapter is essential, not only to grasp planning’s ambivalent relationship with slums but also to explain why these constituencies remain politically organized and powerful in contemporary Mumbai.

Mittal Institute: What are the new lessons from the Dharavi redevelopment for architecture and city planning?

Sai Balakrishnan: The new public–private arrangements for Dharavi’s redevelopment exposes capitalist contradictions. Take, for instance, the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR), the land-use instrument that regulates air-rights. The price of TDR is pegged to the price of land. The perversity is that in order to incentivize developers to build “free housing,” land prices (and, by extension, the price of air) must remain as high as possible.

Until the 1980s, the role of planning in a capitalist society was to socialize the access to land for worker housing. Policies such as rent control, social housing, and other planning measures were designed to keep land rents and prices low. In contemporary Mumbai, however, the role of planning has inverted: planning is now aimed at keeping land prices as high as possible so that ‘free housing’ can be provided to the city’s most vulnerable citizens.

In critically unpacking the costs and contradictions of the ‘free housing’ policy, I want to re-politicize land-use planning. Land-use planning instruments like the TDR are not merely technical; instead, they enact political goals. Ordinary architects and planners in South Asia often work with the best of intentions, but when they use these planning instruments uncritically, they can become unwittingly complicit in producing exclusionary cities. Re-politicizing land-use instruments is urgently needed if public resources (like land and air) are to be reclaimed for the public city.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its Steering Committee.