The Mittal Institute is delighted to welcome Rose Sebastian—a researcher with long-standing interests in cultural studies, critical museum studies, and modern India—as the Mittal Institute’s Jamnalal Kaniram Bajaj Fellow. She is also a fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Science, Technology, and Society. Rose spoke with the Mittal Institute about her postdoctoral research project, in which she is exploring science museums in post-independence India.

Rose Sebastian, the Mittal Institute’s Jamnalal Kaniram Bajaj Fellow

Mittal Institute: Welcome to Harvard, Rose! Could you tell us a bit about your research on museums, and what initially drew you to this field of study?

Rose Sebastian: Thank you! The Harvard community has been very welcoming and appreciative of my work. It has made the settling-in process quite smooth.

It is in hindsight that the trajectory of my research becomes clear to me. From childhood, I was fascinated by ways in which people preserved and transmitted personal memories through objects and stories. My specialization in Cultural Studies during the master’s program at the English and Foreign Languages University (Hyderabad, India) enabled me to extrapolate the processes of memory-making from the individual to the collective level. Two courses proved especially formative: ‘The Fiction of India,’ offered by Prof. Satish Poduval, and ‘Reading Foucault,’ offered by Prof. Dilip K. Das. The former helped me decipher various ideas and imaginations of modern India that are encoded in our literary and visual narratives; the latter helped me understand the genealogy of modern institutions, including the museum, and the institutionalization of certain practices during modernity. Insights from these courses inspired my master’s dissertation, which used case studies of three museums in the city of Hyderabad to examine the question: ‘What is the story of India as told by these museums?’ This inquiry continued to guide my interest and evolved into my Ph.D project under the supervision of Prof. Dilip K. Das on the mutual construction of the nation-state and museum narratives in post-independence India. The dissertation, titled ‘The State Museum in India: Nation, History, and the Politics of Display,’ included case studies of five national-level museums from across the country. These museums were thematically diverse and included museums of history, art & archaeology, science-technology & industry, indigenous peoples & cultures, and museums dedicated to ideas such as democracy.

Mittal Institute: During your postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard, you’re exploring science museums in post-independence India through the lenses of cultural studies and science and technology studies. Could you tell us more about the questions driving this project?

Rose Sebastian: The current project emerged as an offshoot of my doctoral research, during which I observed that science museums in India operated differently from other national museums, say, those of art, history, or archaeology that spoke of India’s past. Science museums in India speak of an aspirational techno-scientific future for the nation. The sensibilities and policies of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, have profoundly influenced post-independence India’s science museums. Nehru contended that while there is no uniquely ‘Indian’ science apart from universal science, science in India must address the basic needs of millions of its citizens. My research focuses on how India’s science museums are shaped by the contingencies of postcoloniality and by the broader post-World War II and the Cold War international milieu.

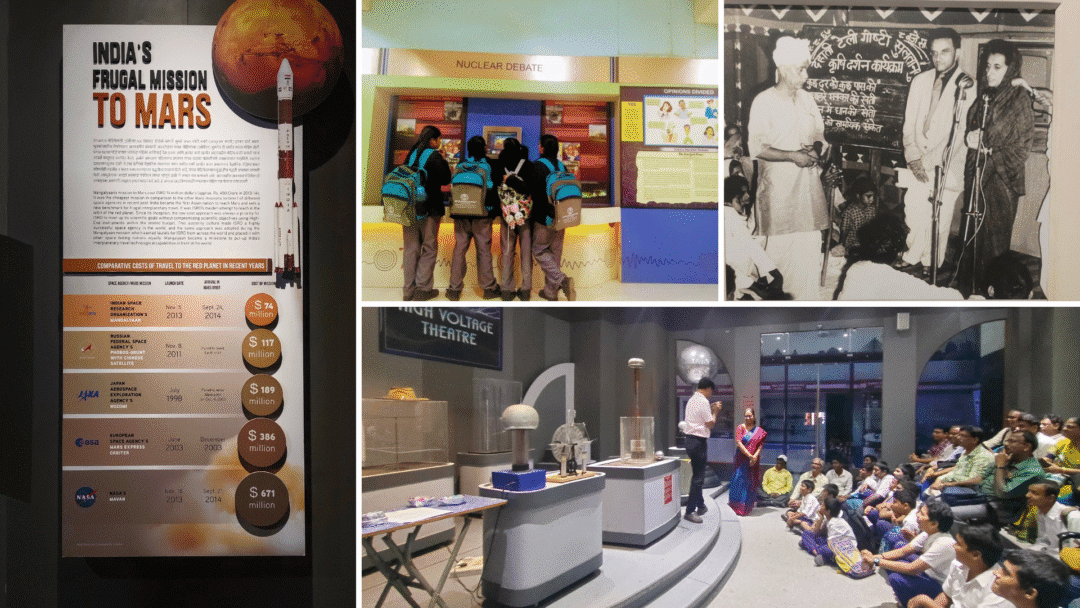

Images of the science museums that Rose will study during her fellowship. Clockwise from left: Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai; VITM, Bangalore; Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai; BITM, Calcutta

Mittal Institute: How is your fellowship with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Science, Technology, and Society (STS) shaping up your work?

Rose Sebastian: My background in cultural studies provided a strong foundation for conducting semiotic and textual analyses of science museums. I started off doing some preliminary work of this kind. But I also wanted to explore how science museums spoke to society and vice versa – the relation between an institution and its intended public. I thought it would be a rewarding project to situate the functioning of science museums alongside questions of democracy. The inquiry required a sociological approach as well. After completing my Ph.D, I began teaching full-time in a college while simultaneously pursuing my research interests in science museums. In 2024, I had the opportunity to meet Prof. Kaushik Sunder Rajan, who introduced me to the interdisciplinary field of Science and Technology Studies. He brought up some initial thoughts for me to ponder, for instance, the distinctively Indian constitutional imagination of scientific temper as a fundamental duty of citizens. Upon knowing about my Mittal Institute Fellowship to Harvard, he encouraged me to participate in the Kennedy School’s STS Summer School and their Science and Democracy Network Meet in August 2025. I eventually joined the STS Program as a fellow.

The STS Program, pioneered by Prof. Sheila Jasanoff, has been a perspective-altering experience for me. It equips me to ask fundamental questions about the very idea of science and the ‘scientific truth’, about the boundaries between scientific and non-scientific domains. These were entities that I had previously taken for granted. The STS Program gives me the analytical tools to interpret and a vocabulary to articulate what had previously caught my attention as ‘amusing instances’ from Indian science museums. Prof. Jasanoff’s conceptualizations of the co-production of science and society, and sociotechnical imaginaries are immensely valuable in understanding the distinctive characteristics of Indian science museums within their specific socio-political and economic contexts that I previously spoke of. The program has also broadened my perspective by exposing me to leading thinkers from the field of sociology of science and scientific knowledge.

My project is yet evolving but as I see it at this moment, it will have two interlinked key aspects: one of STS and one of postcoloniality. Conversations with Prof. Jasanoff and Prof. Homi Bhabha – the pioneers in these domains respectively — have given me direction and confidence in the relevance of my project.

Mittal Institute: You are a two-time Charles Wallace Fellow in the U.K., where you conducted a case study of the Science Museum London and archival research in the British Library. What insights did you gain by comparing Indian science museums with the Science Museum London?

Rose Sebastian:Both institutions clearly emerged from distinct conceptualizations of the role of museums and science within their respective societies, shaped by specific historical contexts. I am still working on situating the data collected from the Science Museum London within a comparative framework to draw conclusive insights. However, some provisional observations can be made: the London Science Museum appears to prioritize public engagement with science and technology. There are elaborate displays on the history of science and technology, Britain’s contributions to the scientific world, an almost celebratory narrative dedicated to the industrial revolution and its driving force — the steam engine, among others. Indian science museums have focused on literacy in science and technology, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s when the earliest state-founded science museums were being set up. One could say that in the latter half of the twentieth century, the London Science Museum was competing with the television to engage with its public, whereas Indian science museums functioned more as extensions of classroom teaching. This difference is evident in their outreach activities, newsletters, and public events.

Mittal Institute: How do you envision science museums evolving in India over the next decade, especially with digital technologies and climate challenges?

Rose Sebastian: Currently, the content and operations of all national science museums in India are largely uniform, as they are centrally coordinated by the National Council of Science Museums (NCSM) under the Ministry of Culture. This centralized framework may have been effective during a particular historical period to achieve the intended social outcomes of these institutions. While individual museums have introduced a few additional galleries and displays over time, the overarching structure and modus operandi remain uniform and largely unchanged. As the societal requirements and challenges evolve over time, it becomes imperative to diversify each of India’s science museums to cater to the demands of various kinds of audiences. Galleries on basic machines and electricity might continue to be pertinent for some centres, but may have become redundant for some others; interactive and experiential exhibits on topics such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality will be hugely appealing in some sites. Moreover, all museums could consider integrating dialogues on areas such as public health, wellbeing, climate change, and ecology. This diversification and updating should not be limited to the thematic content but extend to the form and function of museums. Science Gallery Bengaluru is viewed by many as an exemplar in innovative science communication in India.

As the societal requirements and challenges evolve over time, it becomes imperative to diversify each of India’s science museums to cater to the demands of various kinds of audiences.

Mittal Institute: What excites you most about your fellowship?

Rose Sebastian: I look forward to learning from some of the best minds of our times and my interactions so far with Harvard scholars and teachers have been invaluable. The research ecosystem here comes across as appreciative and nourishing. It is the immensity of academic resources at Harvard that excites me the most. I also intend to gain exposure to science museums in the US. I plan to travel to Washington D.C. to visit some of the Smithsonian museums.

This semester, I have also signed up for Harvard STS’s Graduate Advanced course on ‘Science, Power, and Politics.’ After a few years of being a teacher, it feels good to be a student again, that too in a highly interactive, diverse, and cosmopolitan classroom with diverse perspectives. The participants of the class come from a wide range of disciplinary and career backgrounds, which enriches the discussions and thought processes. It is beautiful and I enjoy my classes.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its steering committee.