Tresa Abraham, a cultural historian of colonial South Asia with a foundation in literary studies, is the Mittal Institute’s newest Raghunathan Family Fellow. Tresa’s research focus is on the use of wild animals in power negotiations in colonial India. Trained in English literary studies, she approaches the colonial past with a literary lens, weaving together histories of animals, humans, and the empire. We spoke with Tresa about her research, and what she hopes to focus on during her fellowship at Harvard.

Tresa Abraham, Mittal Institute Raghunathan Family Fellow

Mittal Institute: Welcome, Tresa! What first drew you to colonial culture and, specifically, to the role of wild animals in power negotiations in colonial India?

Tresa Abraham: Thank you. I am excited to be here. My childhood in the late 1990s and early 2000s was spent in Yercaud, a hill station in Tamil Nadu. Colonial estate houses were very common in the area. These houses, with long verandas, often displayed animal trophies. Over time, however, these displays slowly disappeared. With regulations requiring licensing for private possession of trophies, what had once been casually displayed became legally sensitive, and having such trophies was no longer seen as a mark of status—it was considered a liability of sorts.

I believe these early experiences sparked my interest in the colonial period and hunting and taxidermy in particular. Later, as I went into research, I became interested in the why, the how, and the afterlives of these activities.

Mittal Institute: How has your training in English literary studies shaped the way you approach historical material?

Tresa Abraham: My training in literary and cultural studies really shapes how I approach historical archives. I read taxidermy invoices, museum catalogues, official memos, and newspaper reports much like I would read a literary text—paying attention to voice, genre, and the strategic additions, omissions, and framings that structure a narrative. I also look at how these narrative structures shift over time: for example, how firms like the Van Ingens moved from calling themselves “Practical Taxidermists” to “Artists in Taxidermy,” and in opposition to their competition the Theobald Brothers, who used “Naturalists and Taxidermists,” revealing changing ideas about science and craft. This approach helps me see how colonial and princely actors crafted authority. It also allows me to notice moments where animals themselves disrupted these carefully constructed stories. And, it has definitely made me a better storyteller because it pushes me to think carefully about how I assemble and present the histories I work with.

Mittal Institute: While at Harvard, you intend to study the cultural history of taxidermy in India. Can you share more about this research topic and what you hope to accomplish while in Cambridge?

Tresa Abraham: While at Harvard, I am working on the cultural history of taxidermy in India. We tend to hear that taxidermy was something the Europeans introduced and perfected, but the picture is far more layered. Indian kings, local taxidermists, sportsmen, and colonial administrators all shaped the practice, and there were unexpected collaborations — not just among different European empires, but later with American taxidermists as well. Formal and informal networks, ranging from museum connections to personal relationships between hunters, naturalists, and practitioners, played a major role in how knowledge circulated. I’m also interested in how Indian rulers used taxidermy diplomatically and to craft identities that fit colonial and native ideals of Indian kingship.

We tend to hear that taxidermy was something the Europeans introduced and perfected, but the picture is far more layered. Indian kings, local taxidermists, sportsmen, and colonial administrators all shaped the practice, and there were unexpected collaborations.

Importantly, the practice itself shaped social and cultural dynamics within India. Taxidermy elevated white sportsmen within colonial hierarchies, framing them as ‘men of science’ in opposition to native “stuffers” and those who hunted merely for pot. At the same time, Indian kings strategically used taxidermy as a diplomatic tool and to project their royal identity and sovereignty. However, the caste and race based hierarchies reinforced negative perceptions of native practitioners, who were excluded from the cultural and symbolic capital the craft could confer. Instead, they were further marginalized by both colonial and indigenous elites.

While in Cambridge, I want to pull all this material together and give the project a strong conceptual foundation. Because I arrived late, I couldn’t take fall classes, so I plan to attend courses in the History of Science and in material culture in the spring to build the theoretical grounding I need. I also intend to visit various Natural History museums, such as the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian museums, that are crucial to this research.

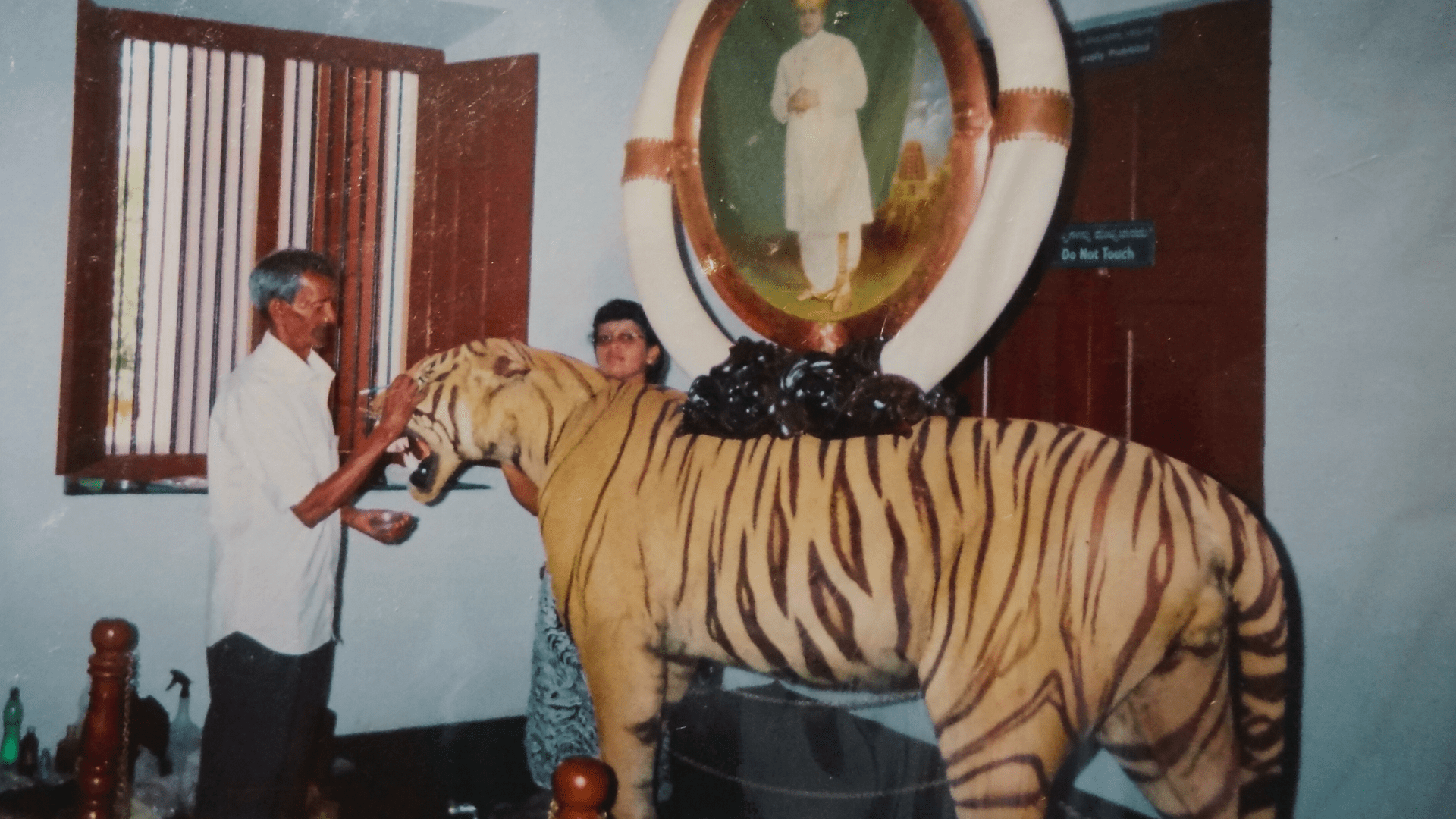

The Trophy Room at Amba Vilas Palace, Mysore | Photo courtesy Tresa Abraham.

Mittal Institute: How have Indian practices and attitudes toward taxidermy evolved or changed over the years?

Tresa Abraham: Taxidermy as a profession has always had limited acceptance in India, mainly because of caste hierarchies and stigma. During my fieldwork in museums, I noticed that public reactions to taxidermy are mixed: some see it simply as a colonial craft, others are horrified by past killings, and while a few recalls colonial hunters such as Jim Corbett, Kenneth Anderson, who aided the colonial state in “managing” these big-cats through hunting.

Crucially for my project, however, is the state’s shifting stance on taxidermy. With India ratifying CITES in 1976, many taxidermy firms began to slowly close their doors, and numerous taxidermists were left with only the maintenance of existing trophies. Having wild animal trophies became a liability. Around 2010, the Maharashtra government established a taxidermy center at Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Borivali, aiming to use taxidermy for wildlife education, but only preserving animals that died naturally in zoos or sanctuaries. This is in opposition to the European world that is moving away from the use of taxidermy for conservation education.

Taxidermists at work | Photo from Manjula’s collection.

Taxidermy Center at Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Borivali | Photo courtesy Tresa Abraham.

Mittal Institute: What does the cultural history of taxidermy reveal about shifting ideas of science and empire in India?

Tresa Abraham: I am attempting to build on Kapil Raj’s idea of contact zones being an active site of knowledge-making. My project shows how taxidermy in India was shaped through multi-imperial and transatlantic networks—Dutch, French, Spanish, British, and American—and how Indian rulers, artisans, and colonial administrators negotiated power, identity, and scientific authority through this practice. In doing so, I recover the contributions of marginalized native practitioners, highlight the role of informal networks, and examine how caste, race, and sovereignty were deeply embedded in the circulation of this scientific craft.

I am still refining this project and am certain it will undergo many changes during the course of the fellowship. I am confident that learning from the courses, seminars, and peer discussions at Harvard will help me shape it further.

Mittal Institute: What are you most looking forward to during your time at Harvard?

Tresa Abraham: As this project sits squarely within the history of science and material culture, I’m excited to take courses that will give me the conceptual grounding I have never formally had. Beyond coursework, I’m really looking forward to the conversations—seminars, peer discussions, and the everyday intellectual exchanges that inevitably reshape a project in unexpected ways. I’m also putting together a small reading group on animal history, which I hope will become a collaborative space to work through some of the conceptual and comparative questions in my research.

I will also be visiting the Smithsonian Museums and the American Museum of Natural History in December, which is especially meaningful because both institutions are central to the transnational networks I’m tracing. Most of all, I’m looking forward to time: time to sit with a decade’s worth of archival material, refine my arguments, and let the project evolve over the year.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its steering committee.