The Mittal Institute concludes its fall event lineup with “Colonial Surveillance in Asia,” a December 19 seminar that will explore the persistence and evolution of colonial surveillance in Asia. The conference is chaired by Sugata Bose, Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs, Harvard University and Radhika Singha, Retd. Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Visiting Professor at Shiv Nadar University. It features presentations from P. Arun, Mittal Institute India Fellow 2025; Midori Ogaswara,University of Victoria; Robert Rahman Raman, SRM University Andhra Pradesh; and Javed Iqbal Wani, Dr. B.R Ambedkar University Delhi. We spoke with P. Arun, who previewed the conference and gave some insights into colonial surveillance practices in South Asia.

P. Arun, Mittal Institute India Fellow 2025

Mittal Institute: How do you define “colonial surveillance” in the South Asian context, and what distinguishes it from other forms of surveillance used in non-colonial setting?

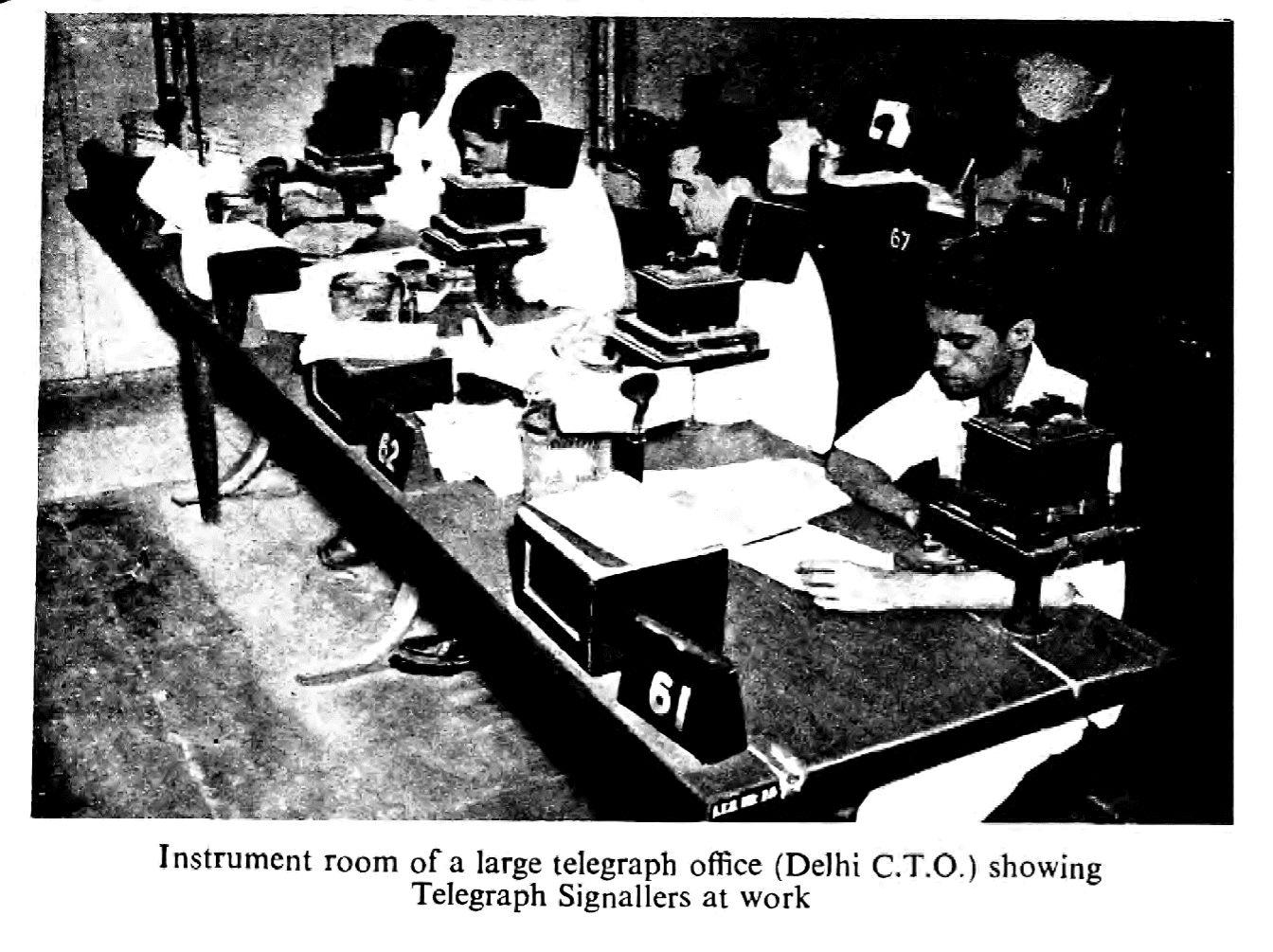

P. Arun: Colonial surveillance in South Asia was an indispensable, multifaceted, and often repressive mechanism of imperial rule. It can be defined by its features, which were authoritarian in its aim to maintain sovereign control, suppress dissent, and acquire knowledge about the colonial territory. Among many colonial laws, the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 was the most draconian and repressive as it had explicit codification of sweeping powers to intercept, monitor and censor postal and telegraph communications of the colonial subjects and anti-colonial activists. This can be distinguished from surveillance in metropolitan Britain, where it was considered a royal prerogative and was not explicitly codified power. In post-colonial India, colonial surveillance practices were adopted and persisted within a democratic framework, paving the way for modern surveillance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This continuity is evident in the replacement of the century-old Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 with the Telecommunications Act of 2023, which retained and even expanded these surveillance powers.

Mittal Institute: How did surveillance tactics vary across locations, and what factors most significantly shaped these variations?

P. Arun: Colonial surveillance was not uniform across Asia; it was adapted to local contexts and often took repressive, coercive, racialized, and gendered forms. There were variations across colonies which were shaped by the imperial need for control and the anxiety of governing territories perceived as unstable. For example, Midori Ogasawara shows how in Japanese-occupied Northeast China, surveillance relied on biometric techniques such as fingerprinting for identification and labor control. This system categorized people into ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ bodies, with those on a blacklist denied employment. In contrast, my research on British India shows how anti-colonial movements and transnational threats such as communism shaped surveillance practices over postal and telegraph communications, all in service of maintaining imperial control.

Mittal Institute: Which forms of surveillance proved most effective for colonial regimes, and why?

P. Arun: Colonial regimes used several surveillance measures to maintain their control, including communications surveillance over telegraph and postal correspondence. It would be inaccurate to regard them most effective, but it was fairly effective to stem the imperial anxiety, fear and panic in first half of twentieth century. Telegraph and postal system under the control of British Raj allowed colonial authorities to intercept and censor messages aimed to prevent communications between anticolonial and communist leaders. Monitoring letters helped them track national leaders and underground movements. Informant networks often drawn from local communities gave inside information about everyday resistance, making surveillance personal and pervasive. In short, surveillance enabled the tracking of networks, connections and movements of those engaged in challenging authority of the British Raj.

Surveillance enabled the tracking of networks, connections and movements of those engaged in challenging authority of the British Raj.

Mittal Institute: How did local populations resist, evade, or repurpose surveillance systems imposed upon them?

P. Arun: Colonial subjects and anti-colonial activists developed creative strategies to resist and evade colonial surveillance. While the British introduced the telegraph and postal systems to strengthen imperial control, these networks were repurposed for anti-colonial resistance and the freedom movement. Activists and leaders relied heavily on telegraph and postal communications. In order to protect their correspondence from the constant watch, they employed anti-surveillance measures such as coded language, cover addresses, and aliases to conceal their messages. For instance, Subhas Chandra Bose corresponded with his wife Emilie Schenkl using the identity ‘Orlando Mazzotta.’ Secret couriers and informal networks were also used to bypass censorship. Through these practices, colonial surveillance was not entirely defeated but was effectively circumvented, thus exposing the limits of such control.

Mittal Institute: In what ways were racial hierarchies incorporated into colonial surveillance in South Asia?

P. Arun: Contrary to the assumption that biological differences necessitated surveillance, it was, in fact, the creation and normalization of social categories through racialized surveillance as what Simone Browne in her book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness describes this as the exercise of “power to define what is in or out of place.” Colonial surveillance in South Asia systematically incorporated caste, religion, and ethnicity into administrative categorizations. The colonial census actively enumerated caste and religion, transforming these fluid identities into fixed social categories for bureaucratic ordering. The legal system reinforced religious distinctions by mandating that civil matters be adjudicated according to religious affiliation. Certain clans and castes were further stigmatized through targeted investigations and designated as “criminal tribes and castes.” Ethnicity also shaped control mechanisms, such as classifying groups like Sikhs as “martial races” for selective military recruitment. Biometric identification systems, including fingerprinting, were initially introduced to identify illiterate subjects of Britain’s imperial possessions and were later applied specifically for racial control against Asian immigrants in the Transvaal.

Mittal Institute: How did postcolonial states inherit, modify, or reject the surveillance infrastructures left by departing empires?

P. Arun: Despite the end of colonial rule, postcolonial India largely inherited—rather than dismantled—the surveillance infrastructure built by the British. After independence, the state continued to rely on colonial-era laws; for example, the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 remained in force and was frequently used to monitor and suppress domestic dissent, much as it had been deployed against anti-colonial activists.

Over time, the postcolonial state modified and modernized these inherited structures, extending their scope. Recent efforts were framed as ‘decolonizing laws,’ which replaced the century-old Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 with the Telecommunications Act of 2023. However, this new telecom law concentrates surveillance powers with the executive, with no effective safeguards. Moreover, it expands surveillance powers which evolved from century old telegraph systems to all modern telecommunications, including encrypted communications. So, rather than dismantling colonial surveillance, it was further modernized. It can be described as a fusion of the intentions of the colonial state and postcolonial state, resulting in a regressive and authoritarian surveillance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its steering committee.