The Mittal Institute is pleased to welcome Fatima Fayyaz, who joins us this spring semester as the Syed Babar Ali Fellow. Fatima is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature and Creative Arts at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). Her research focuses on Persian mystical and epic literature across Iran and the broader Persianate world, including Central Asia, Afghanistan, and South Asia.

During her fellowship at the Mittal Institute, Fatima will undertake a comparative study of āshūrā poetry in Urdu and Persian, tracing its development from the 16th century onward in South Asia and Iran. We spoke with Fatima to learn more about her research and the focus of her fellowship.

Fatima Fayyaz, Mittal Institute Syed Babar Ali Fellow

Mittal Institute: Welcome to Harvard, Fatima! What first drew you to Persian mystical and epic literature, and how did this interest take shape during your doctoral studies?

Fatima Fayyaz: Thank you very much. I am truly honored to be part of the Mittal Institute at Harvard. My engagement with Persian language and literature began in 2009, when I started learning Persian as a graduate student. Early on, I was drawn to Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī and his mystical poetry, which offered me a new way of thinking about human existence and spiritual reality, presenting the ideal of Insān-e Ārmānī (the perfect man) as the ultimate destination and fulfillment of the spiritual quest in the Persian mystical tradition.

During my doctoral studies in Iran, this interest broadened to include Persian epic literature. I came to see that the idea of Insān-e Ārmānī was shaped not only by the concept of beloved in the poetry of mystical figures such as Rūmī, ʿAt̤t̤ār, and Ḥāfiz̤, but also by the heroic virtues embodied by figures like Rostam in the Persian epic Shāhnāmeh. Reading mystical and epic texts side by side allowed me to explore how moral strength, heroism, and spiritual depth together shaped ideals of humanity in Iran and across the wider Persianate world.

Mittal Institute: Your dissertation focused on Central Asian Sufi hagiographies. Can you share more about this research focus, and what surprised you most as you traced connections between Central Asian and Indian mystics in the 15th and 16th centuries?

Fatima Fayyaz: My doctoral research focuses on a sub-branch of the Central Asian Kubraviyyah Sufi order, the Kubraviyyah Hamadāniyyah Ḥusainiyyah, founded by Kamal al-Din Ḥusain Khvārazmī (d. 1551). I examine how his disciples and descendants migrated to the Indian subcontinent and formed close intellectual and spiritual ties with local Sufi communities across different mystical orders.

What surprised me most during my archival research was the depth of these connections. Two of the early seventeenth-century Persian Sufi anthologies reveal, for instance, that Khvārazmī’s son established a khānqāh in Delhi. And Yaʿqūb Ṣarfī (d. 1595), an influential Indian Sufi, became Khvārazmī’s disciple in Samarqand and later composed a maṡnavī about him in Kashmir. These findings highlight a vibrant, transregional Sufi milieu bridging Central Asia and India, opening new directions for understanding Persianate mysticism in the early modern period.

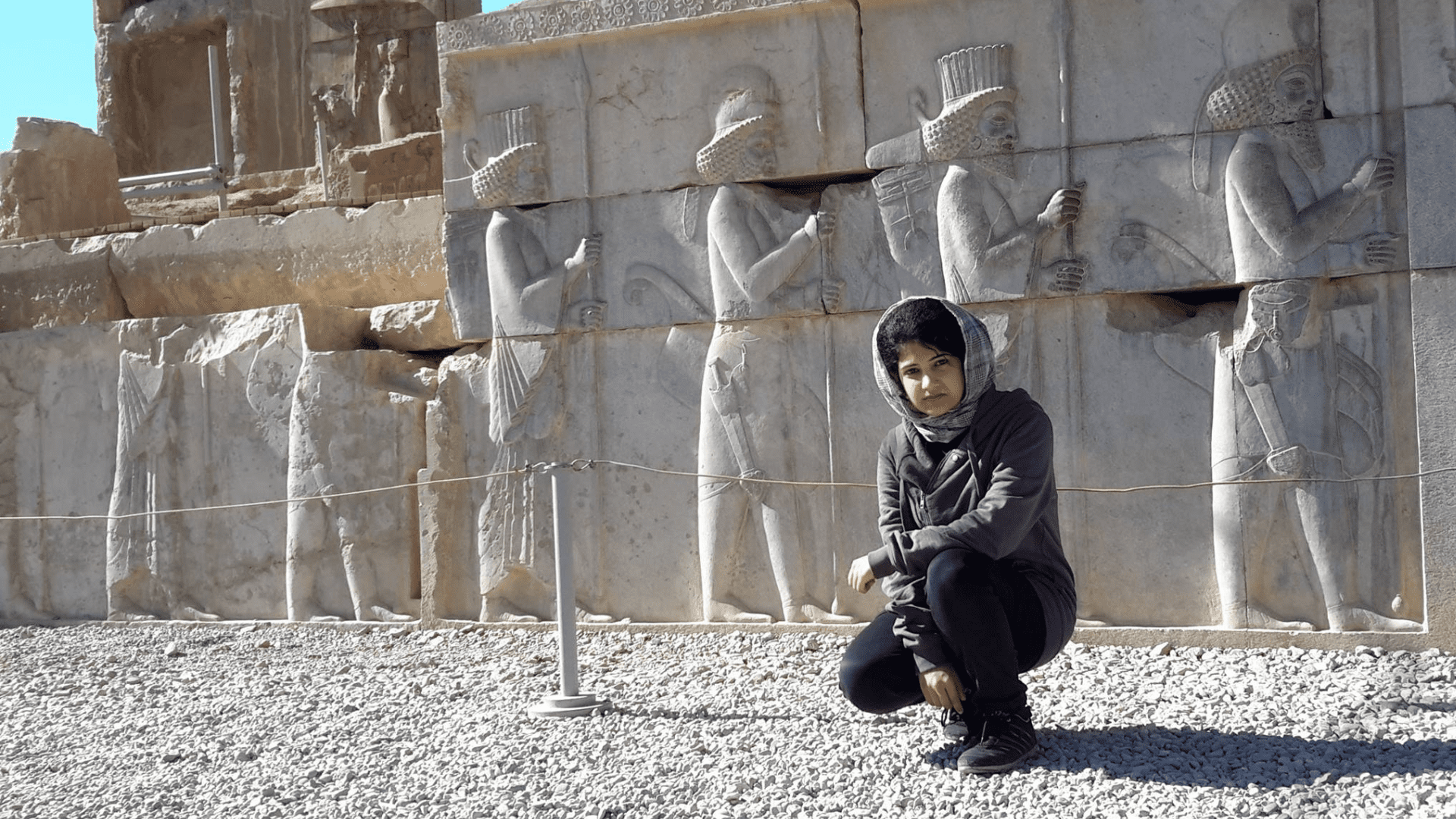

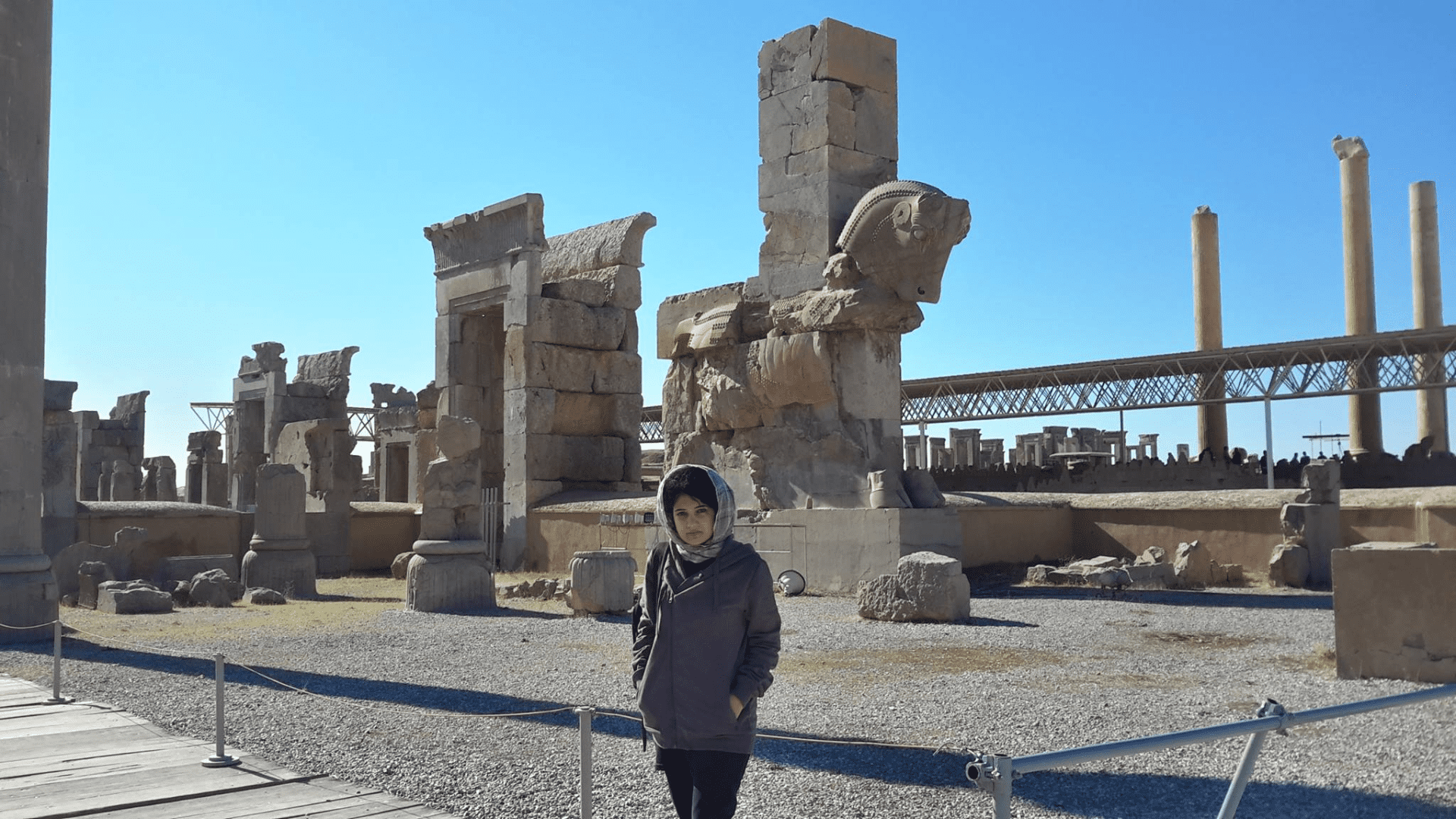

Fatima Fayyaz at Persepolis, Iran, the ceremonial capital of the ancient Achaemenid, Zoroastrian Persian Empire (550–330 BCE) | Photo credit: Seval Gunbal.

Mittal Institute: How does working within a South Asia–focused institute shape or expand the way you approach Persian literary history?

Fatima Fayyaz: Much of my research so far has examined how major classical texts of Persian epic and mystical literature, produced in Iran or within the wider Persianate world, have shaped literary traditions in South Asia. Most recently, I have been working on the influence of Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh and other texts rooted in Iran’s Zoroastrian past on the poetic imagery, historical narrative, and prose style of Ġhālib’s Persian writings, a renowned nineteenth-century Urdu-Persian poet.

Ferdowsi’s statue in front of the College of Literature and Humanities, University of Tehran, surrounded by taʿziyahs, ritual objects commonly carried in Muḥarram processions. The image captures the intersection of Iran’s epic literature and ancient cultural heritage with its contemporary religious identity | Photo credit: Fatima Fayyaz.

Similarly, part of my current research explores how Urdu marṡiyah, particularly in the works of Anīs, draws on the epic imagery of the Shāhnāmeh, especially in the razmiyah sections that depict the battlefield encounters of Imām Ḥusain and his companions. Another strand of my work looks at how Rūmī’s writings inspired the composition of a vast body of mystical literature in South Asia. In this sense, working within a South Asia–focused institute aligns closely with my research interests and allows me to approach Persian literary history through its rich transregional connections.

Mittal Institute: How does your work challenge conventional narratives about South Asian and Iranian literary histories?

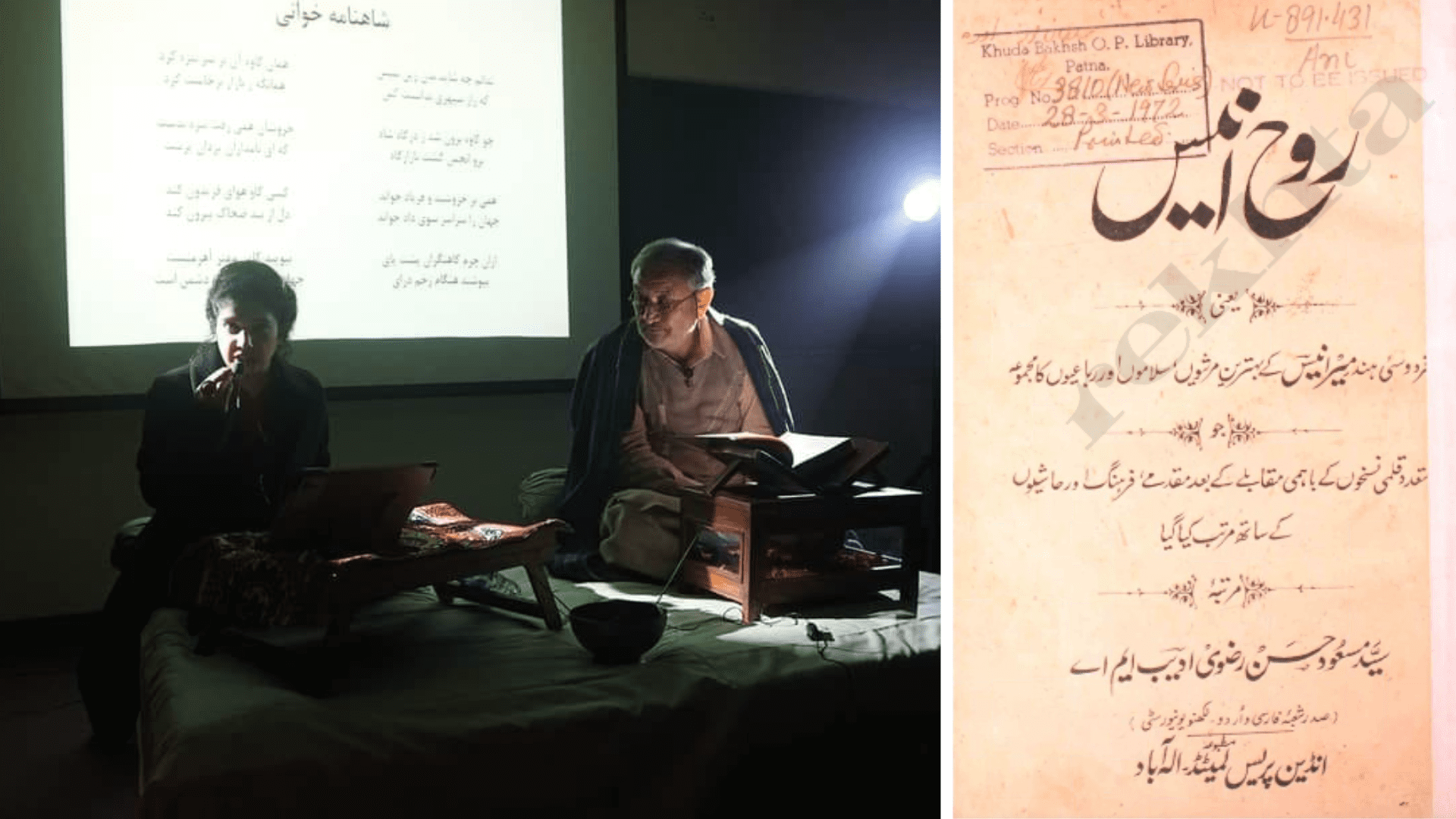

Fatima Fayyaz: I will answer this question by focusing on my current research. While there is significant scholarship on Urdu and Persian marṡiyah separately, there has not yet been a comprehensive comparative study examining where the two traditions intersect and how they may have influenced each other. Many scholars who have studied Urdu marṡiyah argue that, unlike other genres such as the ġhazal, maṡnavī, or qaṣīdah, Urdu marṡiyah evolved independently in the absence of an established Persian model. My research presents an alternate view by focusing on Iranian migrant marṡiyah poets who moved to India during the late Safavid period, became associated with the court in Lucknow and also in Gujrat, and served as immediate predecessors to Mīr Anīs, who later became the most celebrated Urdu marṡiyah poet in nineteenth-century Lucknow.

Marṡiyahs by these migrant Iranian poets are called vāqiʿāt (incidents) because they focus on specific incidents from the battle, and when compared with Mīr Anīs’s marṡiyah, we can see noticeable parallels in theme and style. This comparative approach offers a new lens through which to understand the development of Urdu marṡiyah from nineteenth century to onwards.

Left image: Fatima explains the historical significance of the Shāhnāmeh during a session featuring its recitation in the South Asian Hazāravī style at LUMS University | Photo credit: Gurmani Center, LUMS. Right image: Title page of a collection of selected marṡiyahs by nineteenth century Urdu poet Mīr Anīs, where he is referred to as Ferdowsi-e Hind (the Ferdowsi of India), highlighting the influence of the Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh on South Asian Urdu marṡiyah.

Mittal Institute: What are you most looking forward to during your fellowship at the Mittal Institute, and how do you hope this experience will shape your research going forward?

Fatima Fayyaz: During my time at the Mittal Institute, I am most excited to meet and learn from scholars at Harvard working on Persian literature, comparative literature and religion. I look forward to attending seminars and potentially auditing courses related to my research, which I hope will broaden my conceptual framework.

I also plan to spend a significant amount of time in the Harvard libraries exploring Persian manuscripts and archival materials, not only for my current project but for future research as well. I am especially excited to visit the Metropolitan Museum next month to see the illustrated Shāhnāmeh of Shāh T̤ahmāsp in person. Having used its images extensively in the Shāhnāmeh course I teach at LUMS, it will be a meaningful opportunity to experience the manuscript directly.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the panelists and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its steering committee.