As part of its Annual Symposium, SAI is hosting a series of workshops on April 24 and 25, 2014, to highlight ongoing faculty research projects supported by SAI.

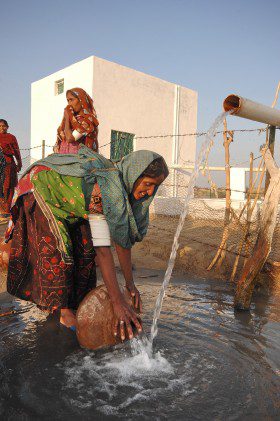

From SAARC to Slums: Urban Water Challenges in South Asia

Friday, April 25, 2014, 8:30 am – 11:00 am

Kennedy Room, Charles Hotel, 1 Bennett St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Register for this workshop.

Faculty lead: Shafiqul Islam, Director, Water Diplomacy Program; Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Engineering; Water Diplomacy, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University

In 2010, the United Nations proclaimed that the world met the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of halving the proportion of people without access to improved sources of water, five years ahead of schedule. They estimated that as of 2011, 768 million people, did not have improved sources for drinking water.

With this metric, we have a success story to celebrate. But we may be celebrating too soon. Where do these people live who lack access to water, and why? What does access mean? What is the difference between improved water and safe water? How does drinking water relate to our total needs for water access? And, more importantly, are water needs truly met for those who have access to improved water?

It’s time to rethink how we measure – and sometimes mis-measure – development progress.

Having access to drinking water equates 20 liters of water per person per day that can be obtained from a source within 1 kilometer from where it is used. Improved water is delivered to communities via infrastructure – like pipes or protected wells.

Looking at 768M without access to improved water, 83% live in rural areas, creating the appearance that water access is predominantly a problem for rural Sub-Saharan Africa, India and China. However, in urban mega slums like Dhaka or Karachi, people pay exorbitant costs for access to water. The 768M statistic does not address the daily reality of water access in these slums.

In the following section, SAI talks to workshop leader Shafiqul Islam about the goals of the April workshop.

Q: What led you to get involved in this topic and research project? Why is it important for South Asia?

A: Providing access to water for an expanding urban population within a stressed and aging water infrastructure creates unprecedented challenges. These challenges are further exacerbated in South Asia by dwindling supply and competing demands, altered precipitation and runoff patterns in a changing climate, fragmented water utility business models, and changing consumer behavior. While scientists and engineers have developed theoretical models of water systems, tools available to implement them have often led to science that is “smart but not wise” because we currently lack the calculus to integrate “scientific learning” with the “political reality” of water problems. Yet, replicable and predictable solutions demand such integration.

Q: What are your goals for the April workshop? What questions are you seeking to answer?

A: For a rapidly urbanizing South Asia with competing – and often conflicting – demands for water, which problems, when addressed, have the greatest potential to make an impact? Can we bridge the divide between theory and practice when natural, societal, and political forces influence water problems? We ask each panel member to articulate a problem and suggest: Why and how does addressing this problem advance science and serve society? What do we need to know to address this problem with measurable outcome? We seek to inspire questions, methodologies and help develop consensus for actionable science with a focus on urban water challenges in South Asia.

A key goal for this workshop is to identify enabling conditions that will facilitate elimination (or reduction) of gaps between “scientifically feasible” and “politically realistic and doable” solutions by exploring urban water challenges over a range of scales from the regional to country to city to the slums.

Q: Why is it important for this project to have participants from a variety of academic fields?

A: There is a growing consensus that solutions to most “wicked” water problems demand integration of scientific learning with the complex political reality of real-world water problem solving. The professionals who attempt to solve water problems cannot easily translate solutions born out of scientific findings into the messy context of the real world. To bridge this divide between theory and practice and resolve complex water problems – where natural, societal, and political elements cross multiple boundaries and interact in unbounded, uncertain and nonlinear way – a new interdisciplinary approach is needed.

Q: What do you hope that the invited participants will contribute to the project?

A: We argue that simply connecting experts, creating more scientific knowledge, developing models and sharing data are not enough to effectively address urban water problems. These problems require water professionals and decision makers to find intervention points where framing of water issues and envisioning of a different water future can be imagined, planned, and executed.

Water users and decision makers need to challenge the belief that water is a scarce resource. Cooperation among governmental and non-governmental actors, and creative problem reframing can make water a flexible resource. Rather than framing decisions in terms of winners and losers for a specific water quantity allocation, we can find creative opportunities that lead to non-zero sum solutions.

Q: After the workshop, what are some of the long and short-term goals for your research project?

A: We contend – similar to Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi when they argued that GDP doesn’t add up to measure our lives – addressing our water problems requires change in how we measure availability and access to water. We need to ask: what do we measure and why does this matter? More importantly, how do our current choices of water allocation relate to present and future consequences they represent?

The choice of treating water as an economic or social good needs to be framed as an allocation problem compounded by distributional complexities related to place, politics, and legacies. We can’t have meaningful dialogues about these choices until we ask more focused questions – Water for whom? at what cost? and at what scale? – and develop short and long term research agenda to create actionable knowledge with measurable outcomes.