This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette

By Corydon Ireland, Harvard Staff Writer

In the spring of 2009, Sheldon Pollock ’71, Ph.D. ’75, the Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies at Columbia, was sitting in a Cambridge café with Sharmila Sen ’92, executive editor at large at theHarvard University Press. “I took out the proverbial napkin,” said Pollock. The two sketched out what would be needed to publish his longtime dream: a series of volumes on classical Indian literature.

Why not 500 books over the next century, they thought: poetry, prose, philosophy, and literary criticism — and later science and mathematics? These largely unseen works, some of which date back more than two millennia, had in the last century shrunk to a canon available almost solely in Sanskrit.

Such a visionary series could bring to light again the heart of the longest continuous multilanguage literary tradition in the world, one that represents the most languages, at least 20 of them. The many languages of the Indian subcontinent, both living and dead, are a musical linguistic litany that includes Sanskrit, Prakrit, Pali, Marathi, Sindhi, Hindi, Tamil, Persian, Telugu, Urdu, Panjabi, and Bangla.

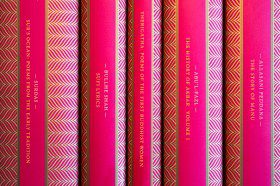

Why not a new series? A model format was already in place. The Loeb Classical Library, launched at Harvard University Press in 1911, now comprises more than 525 handsome volumes in Latin and Greek, along with solid English translations on facing pages. “Back when I was 19 or 20,” said Pollock during a phone conversation, “I very much thought a classical library for India along the lines of the Loeb was a terrific idea.” He called the series an object of “wishing and longing” for decades.

Wishing, longing on a napkin

Sen remembers the same day, when wishing and longing was sketched out on that café napkin. “Shelly told me about the idea,” she said. “I liked it very much. It was exciting to us both.” Sen, who was raised in Kolkata and has a Ph.D. in English from Yale, was aware of a publishing precedent, the Clay Sanskrit Library published by New York University Press, which stopped at 56 volumes.

Its benefactor, investment banker John P. Clay, a onetime honors student at Oxford who studied Avestan, Sanskrit, and Old Persian, died in 2013. (Pollock was co-editor and then editor of the Clay Library.)

A new library of Indian classics, Sen said, would represent all the old languages, including Sanskrit. It would feature attractive and literary translations into English. And it would use the appropriate Indic script on the left-hand page. (The Clay series uses transliterations in Latin script.)

The napkin was full. The idea was good. But where might the money come from to bring it to life? The project, which Pollock described as “the most ambitious ever taken on by an American university press,” needed an endowment, said Sen. “The marketplace doesn’t support these kinds of books.”

Enter Rohan Narayana Murty, with whom Sen and Pollock met in the fall of 2009, when Murty was a Harvard Ph.D. student in computer science. “We had one meeting,” she said. It was enough to convey the series idea and the money it would require. Immediately apparent, she said, was that “this was something very important to Rohan.”

Murty is the scion of a wealthy business family in Bangalore, India, with a history of educational philanthropy. His father is the information technology industrialist N.R. Narayana Murthy, co-founder of Infosys. His mother is the polymath computer scientist, social worker, and author Sudha Murty, India’s best-selling female author, with 136 titles to her credit.

Rohan Murty, now on leave as a junior fellow in the Society of Fellows, knew about the Loeb series, of course, said Sen, and wondered why there wasn’t a version for Indian literature. During his graduate studies at Harvard, Murty took a break from distributed computing and opportunistic wireless networks to delve into courses in the Department of South Asian Studies with Parimal G. Patil, professor of religion and Indian philosophy.

Then came the conclusion of what Sen called “a series of happy accidents,” beginning with that napkin sketch. In 2010, Murty founded the Murty Classical Library of India with a gift of $5.2 million to Harvard.