A family of workers harvests crops near Jaipur, India. Adobe photo.

Each year, the Mittal Institute’s Seed for Change competition encourages Harvard students to develop a vibrant ecosystem for innovation and entrepreneurship in India and Pakistan. Grant prizes are awarded to interdisciplinary student projects that positively impact societal, economic, and environmental issues in India and Pakistan. One Winter 2020 recipient was “Sahayak,” the brainchild of Ambika Malhortra ’20, Aeshna Prasad ’21, Harvard Graduate School of Design alumnae who both earned a Master of Architecture in Urban Design.

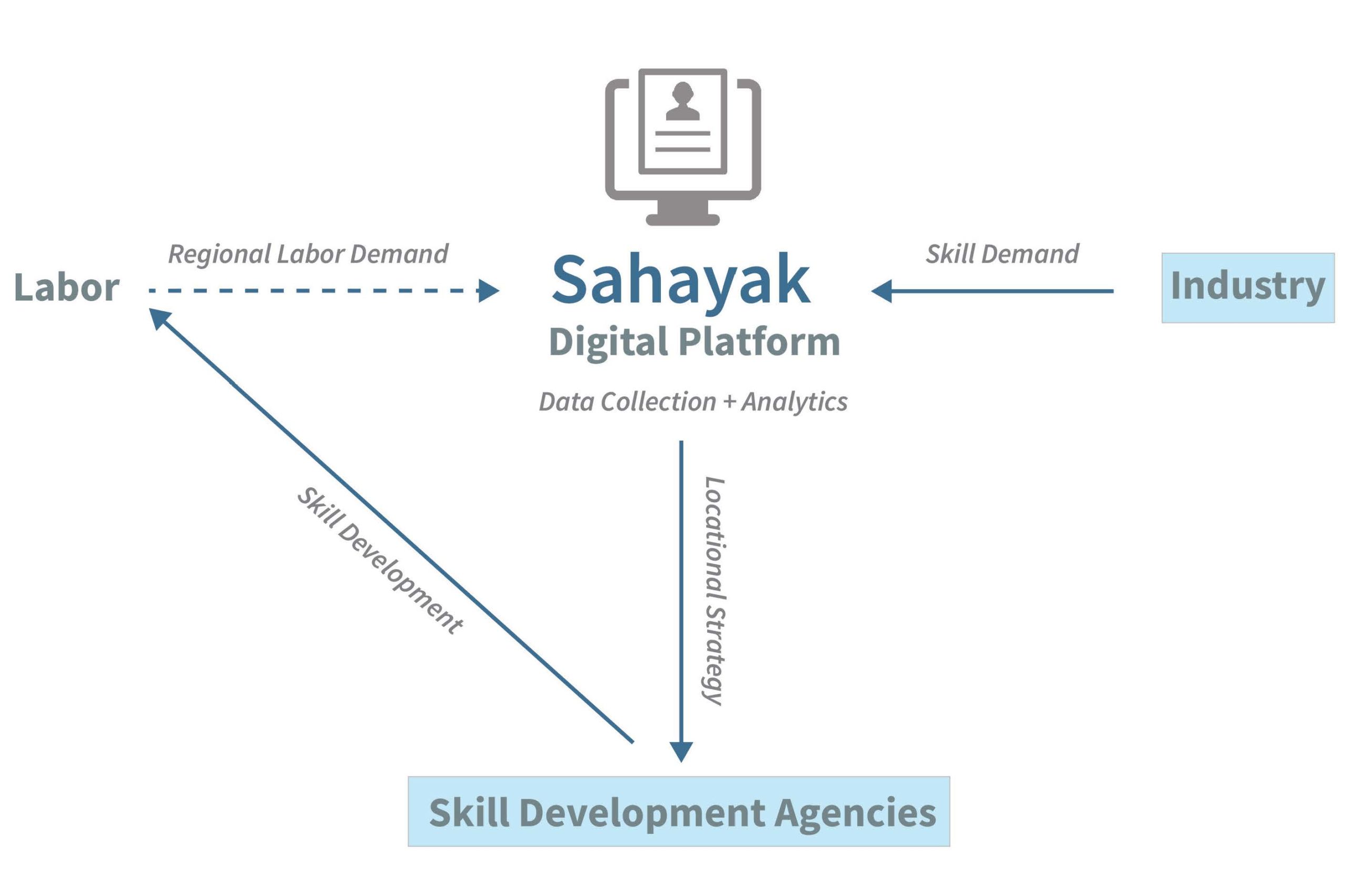

A major challenge in India is to transform the vast number of unemployed and unskilled people in villages into industry-ready workers, while providing job security. Sahayak is a social enterprise that promotes coordinated skill development to industry requirements in rural areas that are currently experiencing transformation. Sahayak takes form as a digital platform that geo-spatially maps industrial needs in an area where individuals are looking for work. Additionally, a physical network of vocational training centers will provide these workers with the necessary skills through the help of locally invested stakeholders. What follows is an excerpt from the report on Sahayak’s progress, in Ambika and Aeshna’s own words.

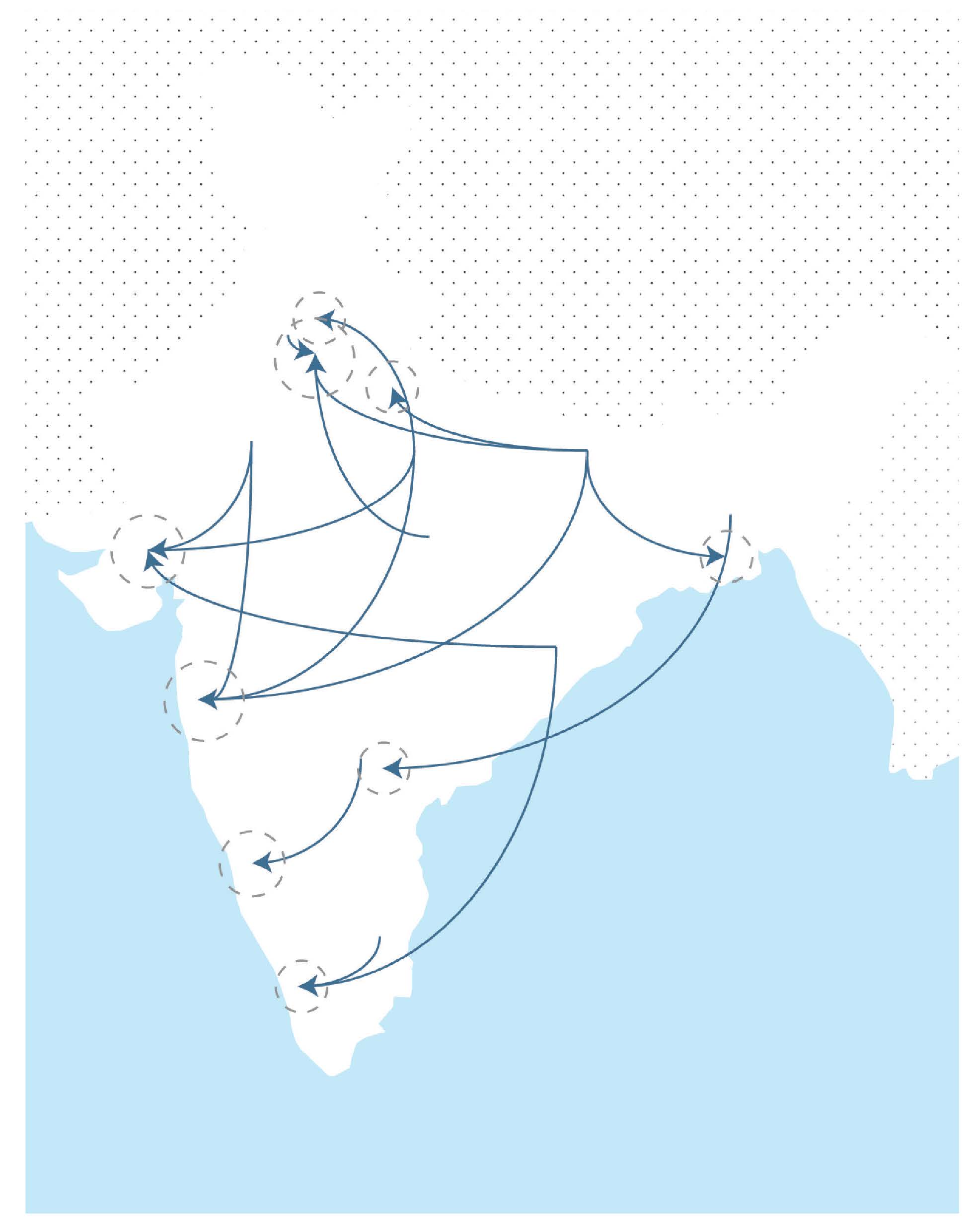

COVID-19 undeniably disrupted the working of cities and countries worldwide to highlight deep-rooted structural inequalities and systemic failures. India witnessed one of the largest mass migrations worldwide within the last year, second to that seen during the struggle for independence. The unemployment rate in India rose to 27.11% in 2020 (The Hindu Staff 2020) in contrast to 6.1% in 2017- 2018 (Bloomberg Quint 2019). The economic disparities forced 51 million in 2011 (Tiwari and Rao 2016) to live without adequate housing in urban settlements, further pressurizing the existing infrastructure of megacities. As urban designers, we have constantly looped back to the question, ‘how can we reduce migration pressures from megacities in India and foster self-sustaining ecosystems?’

India has one of the largest unskilled and unemployed populations globally, which is consistently growing at a rate proportionate to industrial proliferation along new economic corridors like the Golden Quadrilateral Project. However, 116 districts in 6 states (The Wire Staff 2020) have experienced a reverse migration of over one lakh youth per district in 2020. With the second wave in 2021, 8 lakh labors from Delhi itself have reverse migrated to their hometowns (Goswami 2021). It is promptly evident that millions of migrants across the country don’t call megacities home, even after residing in them for decades.

Through our research on labor ecosystems, we realized that many large industries don’t hire from their immediate surrounding or district but rather use brokers to mass transport labor from across the country. While a small group of people migrate to megacities for the urban life, most migrate without their families relevant skills due to desperation and extreme poverty.

Due to COVID-19, 116 districts in 6 states have experienced a reverse migration over 1 lakh youth (approximately 100,000) per district.

About Sahayak

Sahayak connects local industry, skilling agencies, and unskilled labor in rural regions through data collection and analytics to tackle issues of mass migration. We aim to create an ecosystem positively affecting 100 million potential labor migrants.

Vision Statement: Our vision is to reduce migration and housing pressures on megacities by fostering self-sustaining upskilling ecosystems along a trunk infrastructure.

Our explorations made clear that to successfully beta test, we needed to dig deeper into both: the problem at a more manageable and local scale and the system of stakeholders at a more macro-scale. It also helped clarify that Sahayak could not serve as both a digital and physical infrastructure which was what we had originally imagined as the solution, in our proposal. It was much too large a problem for a single venture to handle we came to see. Instead, we chose to capitalize on the locational strategy we identified above and use our own expertise to create a smart mapping system. Alongside is the stakeholder map we worked to create through numerous reports and interviews of people working in the skill development ministry. The aim of creating a stakeholder map was to identify the main decision-makers with whom Sahayak might align itself. We spent a lot of our time focused on the details of our selected state, Odisha more specifically.

Having gained a picture of the system we hoped to intervene within, we then zoomed into Odisha alone and began working with locals to understand how Sahayak might be perceived and received by the various components of the upskilling and labor system.

Interviews included those of unskilled and daily wage labor, HR heads of MSME industries, and government officials at the state and district levels. We created and deployed surveys (Appendix) for each category to thoroughly analyze the curriculum, certification process, funding, course selection, direct and indirect hiring which helped alter some of our pre-existing biases. Responses unanimously indicated urgent demand for our venture, Sahayak and helped inform our product’s evolution.

The main pain point we identified and now chose to address is the skill mismatch between industry requirements and the range of courses by the government skilling agencies. For example, with a high demand for a type of welder was stated by the local automobile industries, the skilling agencies were only upskilling plumbers. With multiple plumbers graduating with no job in hand, a majority are forced to migrate to other parts of the country in a desperate search for work. Thus, we also began studying locations of the skilling institutes set up and their relationship to demand from industry and supply of labor. This would help inform the value Sahayak could provide for we imagine that in the future, government skilling agencies and industries will employ our data services to inform growth strategies.

With the LMSAI Seed for Change Exploratory Grant, we have successfully reduced the scope of the venture, identified pain points to assess product-market fit, and selected our districts, Ganjam and Angul in Odisha to check product demand and validity through on-ground research. The grant enabled us to enlist local research liaisons who served as a critical connection and helped collect first-hand data from the community, given their knowledge of local practices, areas and languages. An example of a game-changing insight they helped reach: we had originally planned to focus on Ganjam alone as our site for piloting this venture, however their explorations uncovered the fact that industrial growth in Ganjam is only planned on paper and conditions on ground are much different from those found through remote research.

The Conclusion

On the 15th of February, 2021 (Singh 2021), India deregulated map-making, clearing obstacles originally expected in access to data. It also made Sahayak commercially viable and less liable on numerous fronts. The second wave in April 2021 hindered on-ground data collection and interviews, but we hope to restart once we have a fully vaccinated team in Odisha. We are currently testing implementation methods for the mapping system using GIS data that informs coordinated skill development. In the next few months, we aim to identify a value proposition for the selected stakeholder and collect micro-level data. We will visit industrial estates and juxtaposed villages to interview migrant workers who are unavailable digitally for beta testing.

As urban designers, we recognize the need for the proliferation of self-sustaining upskilling ecosystems outside a city to balance the growing demands of the country and reduce housing pressure in urban regions. The SFC grant has allowed us not only to scope-down our venture to a manageable size but also reach much closer to our goal of piloting our platform in Odisha at the earliest. It also helped understand this: while Sahayak’s target audience is unskilled labor, in reality it attempts to build a system of mutualism where all involved are bound to benefit and thus must be actively involved with the process.