This is the first blog post in a series from students enrolled in the course ‘Contemporary South Asia: Entrepreneurial Solutions to Intractable Social and Economic Problems’ taught by SAI Director Tarun Khanna. The course features several modules on issues facing South Asia, each taught by a different faculty member.

This week’s focus: Urbanism with Rahul Mehrotra, Professor of Urban Planning and Design and Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, Graduate School of Design.

By Siddarth Nagaraj, MALD Candidate, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy,Tufts University

By Siddarth Nagaraj, MALD Candidate, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy,Tufts University

Are the protection of culture through urban conservation and the pursuit of positive change through development mutually exclusive? Certain traditional schools of thought in urban planning seem to promote that view.

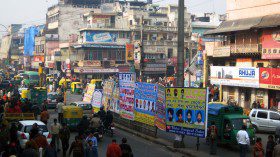

Yet as Professor Rahul Mehrotra conveyed to us in his fascinating lectures this week, even in rapidly growing megacities dominated by a prevailing mindset that equates redevelopment and new construction with economic growth and reform, on can still protect culturally significant spaces and change how we understand urban conservation.

Yet as Professor Rahul Mehrotra conveyed to us in his fascinating lectures this week, even in rapidly growing megacities dominated by a prevailing mindset that equates redevelopment and new construction with economic growth and reform, on can still protect culturally significant spaces and change how we understand urban conservation.

Urban conservation is rarely seen as a public priority by developing nations’ policymakers or the citizens whom they represent. Many regard projects geared towards conservation or heritage tourism to be strange preoccupations of elites, academics and foreigners that are obstructive to economic progress.

For urban conservation initiatives to be more prevalent and successful in Mumbai, there must be a shift in how residents perceive conservation as a concept and as an applied behavior within the context of their city.

I have often felt aggrieved by what I always viewed as a phenomenon of self-perpetuating cultural decay in which so much of India’s cultural heritage situated in public spaces has either been abandoned or erased from public view out of pervasive, seemingly unshakeable apathy. However, until this week I had not thought too deeply about how urban conservation does actually occur organically in India.

Professor Mehrotra presented the case study of Mumbai’s famous maidan, a famous public ground that is regularly used in diverse ways by Mumbaikars from across the city’s social spectrum, ranging from schoolboy cricketers to wealthy families celebrating weddings. Their daily, informal coordination regarding when and how to use the maidan reminded the entire class that urban conservation is most effective not only when there is direct ownership but when the space in question has meaning in the present.

If Mumbaikars see culturally significant spaces in danger of decay as artifacts, they risk undervaluing them and sacrificing them to new construction. However, if they understand them to be relevant to the present, they will appreciate the need to preserve them for the future.

Many people who do support urban conservation in India (including me) have not fully comprehended this fact. If advocates of conservation want more Indians to understand that their initiatives would not repress growth towards a better future, they must show them that conservation is concerned with sustainability, not stasis. Mumbai cannot strategically preserve its public spaces the way European cities it have done-its very nature is too different to that to be possible.

This week’s classes have increased my appreciation of the reality that if urban conservation is to succeed in an ever-transforming city like Mumbai, residents must believe that spaces worth saving are relevant to the future as well as the past.