Since his time as a SAI Aman Fellow at Harvard last spring, Muhammad Zahir has been busy continuing his work on uncovering the archaeological past of Pakistan.

He has worked with teams exploring early Palaeolithic sites in the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia and in the Soan Valley of Pakistan.

Another project includes the documentation and preservation of the endangered archaeological heritage along the ancient Silk Roads network in Pakistan that ran along the Indus River.

He has also teamed up with Prof. David Reich of the Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, to develop a project to study ancient DNA from excavated graves in north-western Pakistan. If successful, the study would be instrumental in understanding modern and ancient ethnicities in South Asia.

Most recently, Zahir has worked with the Japanese Centre for South Asian Culture Heritage (an umbrella nonprofit organization of Japanese archaeologists, conservationists, and art historians) and the Department of Archaeology at Hazara University, Pakistan, to develop a project for mutual cooperation and development of research projects and the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage of Pakistan.

Along with Mr. Atsushi Noguchi of Meiji University in Japan, Zahir has launched a multidisciplinary project, the “Stable Society Project,” to promote peace and stability in modern Pakistani society by promoting the education, traditions, and culture of Pakistan.

The following article, about the Japanese project to preserve India and Pakistan’s cultural heritage sites, originally appeared in the Japan Times:

NGO tries to save South Asian relics

By Yugo Hirano

From the ancient Indian city of Mohenjo-daro to Buddhist Gandhara art, South Asia is rich in cultural heritage but under threat from economic sprawl and a lack of restoration capabilities.

To help preserve cultural sites at risk, a group of Japanese archaeologists has set up a nonprofit organization to provide advanced equipment and pass on their know-how.

Pakistan and India, for example, have numerous cultural heritage sites. With the exception of a few famous ones, however, most are little known globally and international aid is limited. Local authorities face financial constraints and in some cases are neglecting or abandoning sites.

Fearing the loss of heritage to the surge in land development in recent years, the Japanese group and other experts launched the Japanese Centre for South Asian Cultural Heritage in October last year.

“Through our network of researchers, we want to provide meticulous support in areas that (local) governments and international organizations can’t get around to,” said Atsushi Noguchi, the NPO’s secretary-general.

The center plans to supply local researchers with such advanced equipment as infrared laser scanners and radio-controlled helicopters for metric documentation and teach them how to use it.

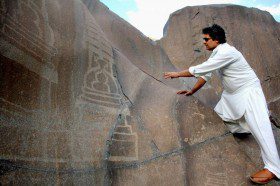

The first project under way involves saving Buddhist artifacts in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region that are expected to be submerged by dam construction.

Preservation of the sites, which include about 30,000 items comprising Buddha statues and pagodas, rock carvings and paintings dating from around 4,000 B.C. to the 10th century A.D., is a top priority as some of the murals have already been destroyed by the dam project. Experts believe there are also numerous cultural assets that haven’t even been identified yet.

In cooperation with Pakistan’s Hazara University, the group will use global positioning systems to record the locations of the cultural assets and document and survey the sites. The center in Tokyo will provide other assistance, such as data analysis.

While Pakistan is an Islamic nation, there are many enthusiastic scholars of Buddhist art.

“The Buddhism that was first introduced to Japan came from this region,” said Noguchi. “It is meaningful for us as Japanese to be involved in this.”