This is part of a series of profiles of Harvard alumni who are young entrepreneurs in South Asia.

This is part of a series of profiles of Harvard alumni who are young entrepreneurs in South Asia.

In developing countries such as Pakistan, many births take place at home and are often attended by unskilled birth attendants in suboptimal conditions. This leads to a prevalence of infections – especially umbilical infections that can lead to life-threatening neonatal sepsis.

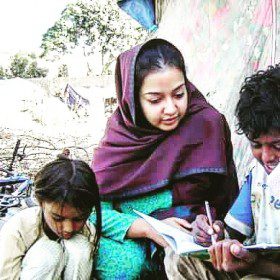

Sabeena Jalal, an alum of Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and currently based in Karachi, is trying to do something about it. She has developed a special blade to be used by midwives to cut the umbilical cord. The blade is made of zirconia, which prevents bacteria from growing and does not rust. Jalal hopes that this tool will reduce the rate of infant mortality in developing countries.

SAI recently spoke to Jalal about how she developed the idea, and her experience as a young “entrepreneur” in South Asia.

SAI: Tell me a bit about the background for this product. What problem are you trying to solve?

Sabeena Jalal: When I worked in medicine at a government hospital, I got the idea to develop something that no matter what the environment is – hospital or home – a woman giving birth will be healthy.

There are 200,000 neonatal deaths in Pakistan that occur every year (according to WHO). For many, neonatal sepsis is a big problem. This occurs when the umbilical cord is cut in such a way that the stump gets colonized by bacteria. Birth attendants usually cut the umbilical cord with a stainless steel blade that they tie to their dupatta. Due to a lack of transportation and infrastructure, they often reuse the blade, which is not safe. In Pakistan, there are also some cultural practices that can cause infection. This all leads to greater infant and maternal mortality.

Seeing all of this first hand made me realize that it might be better to work within people’s existing habits and attitudes rather than expect them to change; the blade we developed is exactly the same size and looks the same. The only difference is that it is made out of zirconia, which means that bacteria will not grow on it.

SAI: How did your time at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH) help you develop this idea?

SJ: Before I came to HSPH, I knew I wanted to do something, but I didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted to do or how to go about it. I took a course on global health delivery, and we had people flown in from all over the world. They talked about different health solutions. Those were exciting times.

At HSPH we have great teachers who are doing practical things all over the world. They show us how public health is actually practiced and how sustainable solutions can be applied, particularly in low-income settings. They focus on the idea of involving stakeholders, and encourage us to think of solutions that are outside the box.

SAI: What has the implementation process been like? What kind of reception are you getting?

SJ: We have conducted about 1200 deliveries so far at different hospitals in Karachi with promising results – only 2 infections out of those deliveries, and we used it in low-income settings. We also conducted a randomized control trial on 100 of those deliveries. We are very excited about the results – we were not expecting it to do so well.

SAI: What are some of the biggest challenges that you faced while developing the idea?

SJ: On a personal level, you need grit to keep on working. For example, the first design we made did not work out as well. Initially I questioned myself and wondered whether it would actually work. The process took about six months. At HSPH, they taught us that it might not be a success on the first go, but you should not give up. If you think the idea is worth pursuing, then you have to pursue it with a fervor to make it happen.

When we actually had it [the blade] made, we were really excited, then we had to get it approved by the ethical review committee since we would be conducting a human trial on women. We needed to convince them that it [zirconia] is already used on humans, in plastic surgery and dental implants. Then we needed to have the women agree to be part of the study. That was the challenge of the second phase.

And of course, Pakistan is a bit sensitive when you try to bring something new or change practices. There are challenges but it has been an interesting journey.

SAI: What is next for the project?

SJ: I hope that we can have multiple trials – in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Africa. These are areas that have similar challenges in terms of maternal health and poverty. It needs to be tested in multiple areas to see its effectiveness. If it’s crossing the barriers of cultures, languages, and customs, it can surely be implemented on a wider scale.

SAI: What advice would you give to a student who has an idea or wants to be an entrepreneur?

SJ: There is so much that needs to be done throughout the world. For people coming out of Harvard, the possibilities are limitless. You need to identify which field you want to contribute to, and Harvard will train you and give you all of the skills needed to not give up and pursue your vision.

-Meghan Smith