Krupa Makhija, new Visiting Artist Fellow at the Mittal Institute.

In 1947, British India gained independence, resulting in the subsequent Partition of the nation into two independent states: India and Pakistan. The line of division, based on Muslim and Hindu district majorities, resulted in forced mass migration that split millions of people along religious lines and incited a period of intense violence and loss of life. The traumatic memories of the Partition remain rooted in the public’s psyche, continuing to provoke hostile foreign policies between the two nations today.

Krupa Makhija is of the first generation of her family to be born in post-Partition India, her parents and grandparents having migrated from the Sindh Province of Pakistan during the Partition. She grew up hearing stories of the pre-Partition era, but only after high school and her art education did she become more curious about her culture, language, and identity. “Art education has created a kind of sensitivity in me, to question things about myself,” she says. Krupa takes the experiences she’s been told about from the Partition era and infuses their emotions and symbolism into her artwork to create a larger dialogue.

As one of the Mittal Institute’s new Visiting Artist Fellows, we sat down with Krupa to discuss the Sindhi culture, her inspirations, and the meanings and symbolism behind her art.

Can you tell me about your background, and the importance of the Partition in your artwork?

My culture and language are both in the constitutional minorities in India, because they are actually uprooted from Pakistan and have not been rehabilitated properly in India — and that is why they’re in danger today in India. The Sindhi language itself came to India with Sindhi migrants, and did not exist previously in this part of India since the entire Sindhi community was located in Sindh Province [in Pakistan]. In India, we have official languages in each state. Suppose I belong to Gujarat — Gujarati is the official language of that state. If you go to Maharashtra, Marathi is the official language of that state. But Sindhi does not belong to any state. Because we don’t have any state, it is not an official language in India.

I grew up with a lot of stories [about the Partition] from my grandparents, my father, and my other relatives. It was a very traumatic experience for them, absolutely different for them and absolutely different for me now. Because when it comes to me, I’m not a direct victim of migration. I have not experienced or gone through that violence. But what I’m experiencing today is what I call “Cultural Amnesia” [in my artwork]. That is the major effect of the Partition that I’m going through. It has completely destroyed our culture, our Sindhi ethnicity, and our language, because first generation migrant communities didn’t have much time to transfer literary skills to the next generations, since they were very busy in their settlement and struggle for survival.

We [the Sindhi community] don’t have [our own] schools; there were a few schools for migrants that were established after Partition, but they’re closed now. So we’re supposed to study in either regional language schools or in English schools. [Due to that], we have completely detached from our language, and I think the loss of language is the biggest cause of cultural destruction, because we can’t read our own literature.

What are you trying to convey through your art?

As an artist, I believe that art can’t change the society — but it can do good. It can provoke some issues. I think I’m doing that; I’m trying to raise questions that are completely ignored and I’m trying to recreate a part of history so people can revisit it.

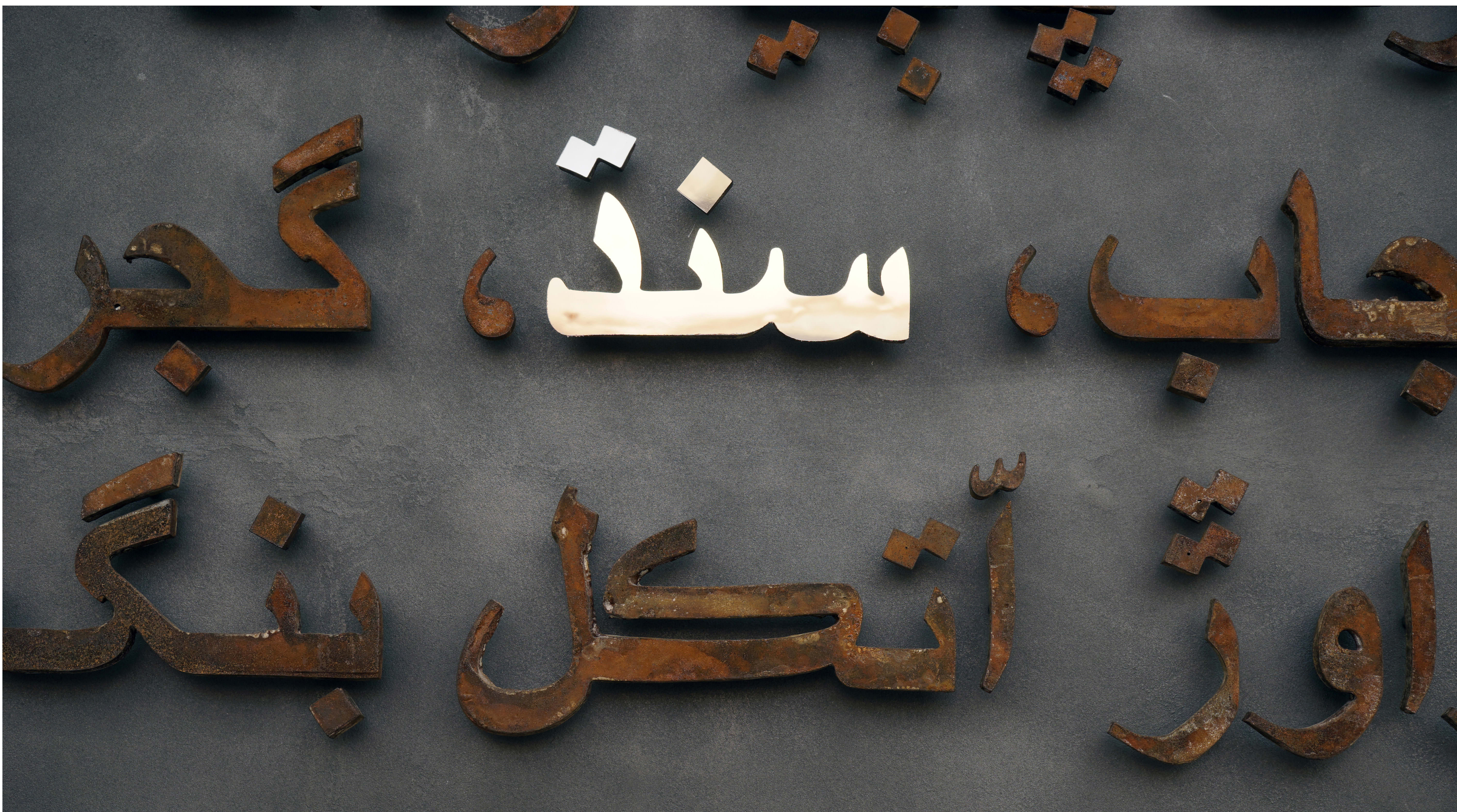

I’m calling [my art series] “An Amnesiac’s Memory.” [The below piece] is entitled “Sindh-Hind.” This is the Indian national anthem, which I have written in Sindhi script. This work is about the controversy to remove the word “Sindh” from the anthem. There is mention of Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat — important regions of India, states that represent the identity of India. This national anthem was written by Rabindranath Tagore before Partition, so there is mention of Sindh. But now people are demanding it be removed from the national anthem, because Sindh is not part of India, it’s part of Pakistan.

“Sindh-Hind” displays the Indian national anthem written in Sindhi script using iron and mirror.

The matter of fact is that the word “Hind” came from ‘Sindh” itself, because Persians cannot pronounce “S” in their native tongue and mispronounce it as “H.” [Because of that], “Sindh” became “Hind,” “Sindhu” became “Hindu,” and India itself got its name from “Indus,” the Indus River, and that is Sindhu. So I wrote [the anthem] in Sindhi script. The word “Sindh” is in mirror, so you can see yourself. It’s like I’m trying to introduce you to yourself.

A close-up of the mirrored portion of “Sindh-Hind” by Krupa Makhija that spells out “Sindh.”

Sindh is a common legacy between India and Pakistan. It is all Indus Valley Civilization, and this is the common legacy that we both share. How could you divide that legacy?

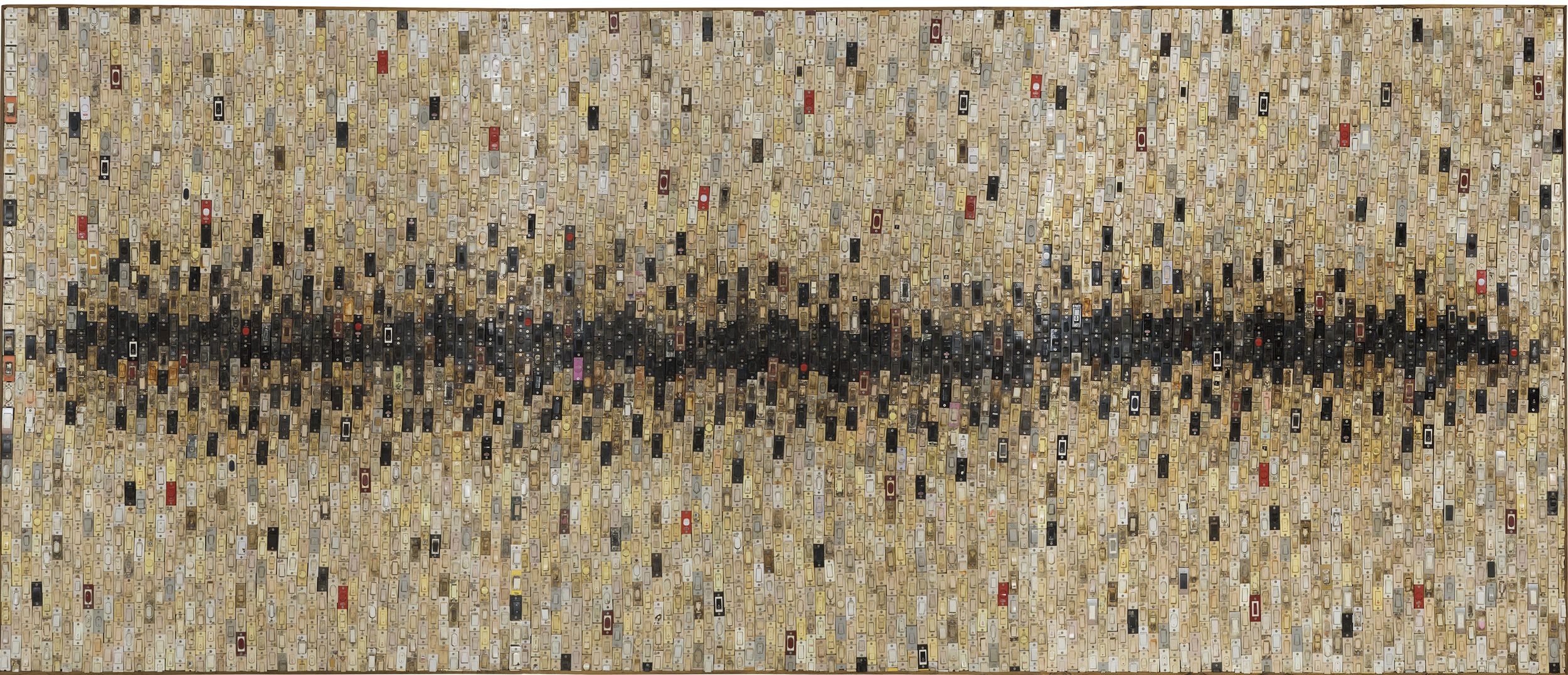

“Witnesses,” 2015-2017. Old found electric switches on board, interactive sound installation.

This [above] is called “Witnesses.” A few years back, the city that I’m currently living in was declared a “smart city,” and the local government went on a demolition drive. They’ve been demolishing large areas. This is something that I have personally seen for the first time in my life. A lot of people are getting displaced and dislocated for development. They have demolished very old, heritage buildings that symbolize culture and traditions. I was visiting the site every day, recording the sounds of the demolition process and watching people, families, kids, and seeing how they got displaced from their homes.

A viewer interacting with the “Witnesses” sound installation.

Somehow during my several visits, I got interested in these switches that were lying in demolition sites. I found them very interesting because they have marks — impressions — that represent the signatures of people and their stories. After two periods, I have collected almost 5,000 switches from various demolition sites and I have created this huge interactive installation that is 12 feet wide and five feet high. The median line black line represents the barricade tape that is commonly used during the demolition process to restrict people from entering the site. There are interactive switches in this median line: if you switch it on, you can hear the sound of demolition process. It’s like I’m inviting viewers to interact with the demolition itself.

I’m still in touch with some of the families. I’m following them and trying to understand the consequences of dislocation. As they migrate from one place to another, how do they carry their own traditions and customs with them?

A close-up of the “Witnesses” installation.

What inspires you to use different, untraditional mediums in your art?

As an artist, I don’t follow any particular style or medium. Anything can be a medium to me. But medium in my work plays a very important role, because I always prefer to choose a medium that can best represent my ideas. I mostly work with found and collected mediums, materials, or objects that have some sort of connection with migrant communities, or are collected by the people, or have traces of memories. Medium itself is a content in my work.

Stones that Krupa has used to create her own pigments.

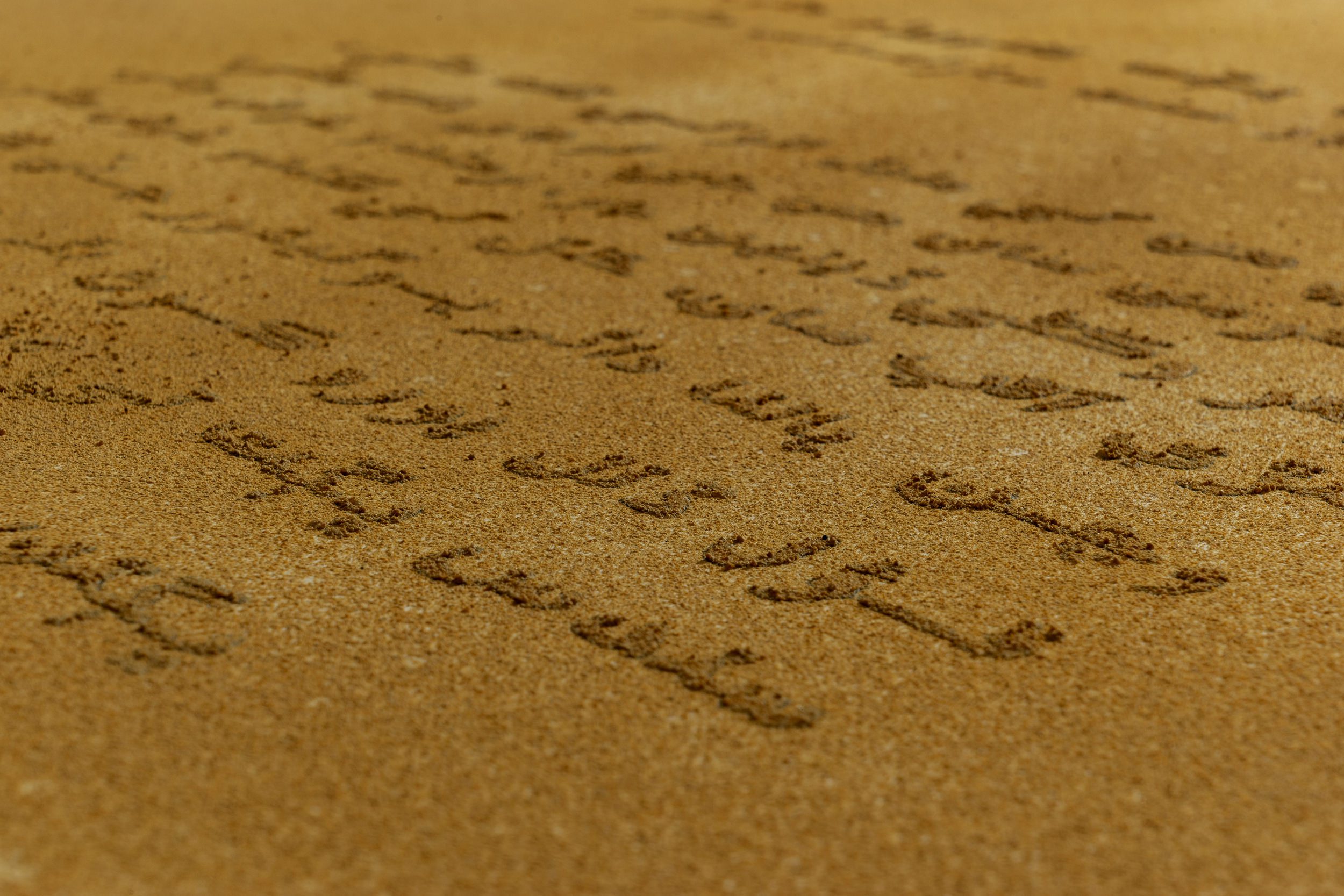

I got interested in stones, because stones are the most ancient material itself; they are witnesses of many histories and important monuments. So I’ve collected stones from many sacred places and from places that have historical importance and I’m recreating Sindhi documents with self-prepared pigments out of these stones. This is the way I’m trying to authenticate those materials and documents, as a commentary on how the Sindhi language needs to be revived.

A close-up of a Sindhi document Krupa recreated using custom pigments she created from collected stones.

Because we have completely detached with the language, we don’t know about our own culture. I’m recreating it with these pigments so people can revisit it and learn about it.

What do you hope to accomplish as a Visiting Artist Fellow?

I’m very much interested in the Mittal Institute’s research into the British Partition of 1947, and how that can inspire my own work. I have gone through the program’s different research areas, like its oral stories and the analysis of urban geography by Professor Rahul Mehrotra — and I’m really excited to learn more about it.

Meet Krupa Makhija on March 12, 2019 at the Harvard Ed Portal exhibition and reception and see more of her artwork on display! Click here for event details.