Chase Van Amburg ‘24, an Integrative Biology concentrator who is also earning a concurrent Master’s degree in Applied Math, specializes in data science with a focus on climate change. This summer he received a grant from the Mittal Institute to begin work on “Mapping Heat in Microenvironments,” and he gave us a glimpse into the essence of his project.

Mittal Institute: Chase, you have done an ecological survey in Kenya and are now working on this climate analytics project in northwest India. What drives your interest in data science and modeling, particularly in vulnerable communities?

Chase Van Amburg: Before coming to Harvard, my dream was always to study ecosystems and the natural world. Almost all of the courses I took in my first couple years in college had something to do with biology, climate, or math. However, when I made it over to Kenya after my sophomore year, I found that the majority of research at the field station ignored the effects of climate on people. Instead, most projects prioritized the study of local plants and animals. This drove me to consider how I could use my background in scientific methodology and data analysis to understand the human experience in the face of nature. Now that I’ve had time to develop these feelings, I hope to continue telling narratives through data to create positive social impact.

Mittal Institute: Can you give our readers an overview of the project? How did you come to work with the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in India?

Chase Van Amburg: I developed this project alongside Professor Satchit Balsari and the Climate Adaptation in South Asia Salata Institute Cluster. The Cluster looks to identify how data can be used and must be collected to effectively respond to growing climate problems throughout South Asia. This summer project focused on collecting microclimate data on the lives of individuals to begin to gather evidence that weather station data is missing a critical part of the story: climate at the scale of a person, not at the scale of a city. To implement this, we would place microclimate sensors within different urban settings to understand how intensely they differ from other existing climate data. Professor Balsari has worked extensively with SEWA on previous research projects during the onset of the pandemic, and they were incredibly generous in facilitating the implementation of this microclimate project. SEWA is based out of Ahmedabad, where I stayed at research housing run by the organization. We ran experiments throughout Ahmedabad and in nearby areas across Gujarat.

This summer project focused on collecting microclimate data on the lives of individuals to begin to gather evidence that weather station data is missing a critical part of the story: climate at the scale of a person, not at the scale of a city.

Mittal Institute: Can you talk about the data collection process, and what you glean from the figures?

Chase Van Amburg: We ran two primary types of experiments. In one case, we would directly follow the climate story of an individual. After hearing the details of the project, a volunteer from SEWA would allow us to place temperature and humidity sensors in her home and workplace. In some cases, volunteers would also wear a body temperature sensor, so we could begin to understand how physiological conditions depended on environmental temperature. In the other type of experiment, we would place multiple sensors around a building, or several nearby buildings, to get data on how different architectural features create distinct microclimates.

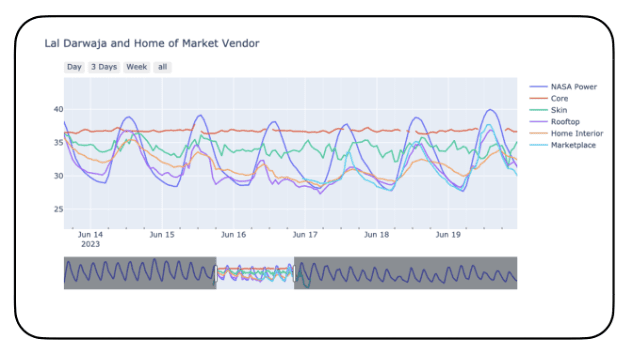

As an example, some figures from a set of observations with Shobhaben are included below. She is a market vendor at a large market near the Sabarmati River in the Old City of Ahmedabad. The data below show that her home and workplace are not unbearably hot during the day, but her home interior remains consistently warmer than the outside environment. At these relatively high temperatures of around 30-40˚C, a few degrees increase at night can drastically affect sleep quality. This is just one of the many insights we gathered from this initial study.

Temperature sensors allow a greater insight into the daily heat exposure of a local woman, Shobhaben.

Mittal Institute: What have been the biggest challenges and greatest successes in working on this project thus far?

Chase Van Amburg: In terms of challenges, this project really draws on a whole variety of disparate disciplines. We need architects, data scientists, physicians, environmental scientists, policymakers, and so many more groups to come together in order to understand urban microclimates. It has been reassuringly easy to find people who are excited about the project and want to collaborate, but hard to align everyone’s research interests in the same focused direction. We need to strike a definite balance in making the research as comprehensive as possible while also designing a realistic project scope. For successes, the fact that the project got off the ground so quickly has been amazing. Thanks to general academic interest and the generous support of the Mittal Institute, we were able to launch this pilot project on short notice. With this initial data collected through the organizational efforts of SEWA, we have a foundation off of which we can launch a much more thorough and larger-scale study of microclimates across South Asia.

Mittal Institute: What are your plans post-graduation? Will you continue to work on this project?

Chase Van Amburg: My journey has taken me through a number of different disciplines, and this has been by far the most exciting research project I have worked on. My experience and interests are very research-oriented; I plan on continuing data science research after graduation. I am currently in the process of applying for a number of academic opportunities for next year just to see what opportunities are out there, but I plan to continue working on this project throughout my final year at Harvard and hope to stay involved afterwards!