Indian photographer Pablo Bartholomew, whose career spans 40 years, has witnessed many of South Asia’s tragedies and triumphs – perhaps most famously the gas tragedy in Bhopal.

Bartholomew was the first artist to come to Harvard as part of SAI’s new Arts Initiative, which brings experienced and emerging artists to Cambridge whose work focus is on social issues related to South Asia, with support from the Donald T. Regan Lecture Fund. His works have been published in the New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Business Week, and National Geographic.

Bartholomow spoke at two SAI events during his week at Harvard. In a seminar on Nov. 4, ‘Anatomy of a Man-Made Disaster: Thirty Years Later, Remembering the Bhopal Gas Tragedy’, he spoke about his first-hand experience documenting the world’s worst industrial disaster. In A Personalized History of Indian Photography, 1880 to 2010, Bartholomow took the audience on a photographic journey in which he shared a collection of Indian photographers who have influenced him.

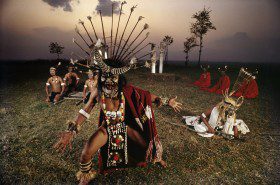

Bartholomew’s exhibit Coded Elegance will be on display at Harvard until Jan. 31, 2015 (CGIS South Concourse, 1730 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA; Open to the public Mondays-Thursdays 7am – 9pm; Fridays 7am – 7pm.) Coded Elegance is a series of ethno-anthropological photographs of tribes and people of the hills and valleys of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Manipur, taken from 1989 to 2000.

READ: Audience reactions to Bartholomew’s photography.

During his visit to Harvard, SAI sat down with Bartholomew to discuss his photo exhibit, the aftermath of the Bhopal tragedy, how photojournalism is changing, and how his South Asian heritage has influenced his work:

Bartholomew’s photo from Bhopal won the 1984 World Press Photo of the Year.

All rights reserved, Pablo Bartholomew

SAI: You said in your seminar on Bhopal that you viewed the victims’ lack of compensation as a “collective failure of the media.” What would success have looked like to you?

PB: Well, success for Bhopal would have been ten times, or a hundred times the volume of money, and the money actually reaching the victims and cutting out all the fraud, red tape, and all the corruption. That’s one part of it. The other, if there was a lot more money and a vision, then the cleanup, which is equally important, could have been completed at a very early stage.

Right now they don’t know what to do with all the chemicals sitting in there. It could have environmental consequences and health issues. There is talk about creating a dump to get rid of the chemicals – but where is that dump going to be? How is it going to be contained? So it’s one of those industrial issues, a modern contemporary issue, that is the same thing as what’s happened in Japan [the earthquake in Fukushima].

SAI: How do you think people are viewing the tragedy now, and how has this changed over time?

PB: People are just now tired. That’s what happens to anything – there’s a fatigue that sets in. It’s the same way that journalism has changed and the media has changed, because you hardly have any hard news anymore – it’s all about lifestyle and fashion, about people’s aspirations, because that’s easier to do, rather than look at the bad and the ugly.

SAI: How has photojournalism changed?

PB: There is no money now for long-term projects which show depth and have density. Right now, everything is about illustration. Now, media is being run by lawyers and bankers. It’s not being run by the old-style editorial people. It’s not just India – I’m talking worldwide, in America and the West. Everything is in flux. Look at Time magazine or Newsweek. And part of it is that the Internet has thrown the media houses into flux, because they didn’t know how to deal with the change and create a revenue model.

SAI: If a tragedy like Bhopal happened this year, would the media have reacted differently?

PB: Well, you would have had a lot more cell phone photos and much more immediate coverage. Citizen journalism would be thriving and active.

Coded Elegance will be on display at Harvard until Jan. 2015.All rights reserved, Pablo Bartholomew.

SAI: For people who are citizen journalists, and post photos on Instagram, there is a debate about whether that is good or bad for photography – what do you think?

PB: I don’t have a problem with any of that personally, because I use this analogy: Everybody can write, but who are the great writers, who can move people with their writing beyond cultural boundaries? It’s the same thing – everybody can photograph and make compelling pictures at a certain moment in time. It’s all a question of here and now. But what they do with their thought process, and how they continue to create year after year, is what matters.

The only thing that bothers me with the blogging and Instagram, is the process of authentication. In a media house, you always have the scenario where the journalist on the field reported, then there were researchers who fact-checked, and there was an editorial layer of what makes a story. That has its upsides and downsides.

SAI: SAI’s Arts Initiative brings artists to Harvard whose work focuses on social change. Can you talk about how you see art or photography playing a role in making social change?

Pablo Bartholomew: I don’t know if social change is possible like a pill, where you take a pill and your headache goes away. I think it’s much more of a very slow process. If people are looking for immediate results, I don’t think that there is going to be that sort of instant gratification. I think any kind of change is a gradual process, and then once you have marked the beginning, then you can see how much progress there is. And of course, people have to be prepared for failure. And that’s one of the humbling aspects, to see how that failure can be gratifying.

SAI: Can you talk about your exhibit [Coded Elegance] that is on display? It’s so vibrant and colorful. What drew you to the Nagas people, and lead you to document them?

PB: Many of my personal bodies of work have a resonance with family. There are 30 Naga tribes between Arunachal, Nagaland, and Manipur, which border Burma to the East and Arunachal on the North borders China. It was originally the Nagas in Nagaland that I went to photograph and discover for myself, because of childhood stories. When my father was escaping the Japanese during the Second World War, and walking to India, he encountered the Naga tribes. Currently, I am trying to find permission to walk the route, the General Stilwell Route, into Burma, a 30-day march that my father walked.

This project has a resonance and family history for me. When I went there [Nagaland], I found this amazingly beautiful people. For other exhibits I have done on the Nagas people, I called them ‘Marked with Beauty.’

This exhibit is called ‘Coded Elegance,’ which points a finger at the fashion industry in India, because this [the Nagas] is true fashion. Every object that they wear, or every piece of fabric or jewelry or marking, has a meaning. You can only get certain markings or wear certain jewelry if you have achieved a certain kind of merit. Everything is very visual. That is why there is a ‘Code.’

SAI: While you were working on the exhibit, did you ever feel like an outsider trying to understand this code?

PB: No – I feel much closer to that end of the world anyway, since my mother is half from Bengal, in the East, and my father is from Burma. I have always been fascinated by tribes, and tribal people. I started to make many friends with the Nagas kids who came to study in Delhi, so there was already a bond. Through them, I learned about their culture.

SAI: How were you received as someone looking to document their culture? Were they open to sharing?

PB: Not necessarily. That’s part of the hardship – it [the photo collection] took me about 10 years, from 1989 to 2000. There is a fair amount of time that I invested in the region. Many of these practices now are ceremonial or hidden.

SAI: Can you talk about the colors – they are so vibrant in this exhibit. On the other hand, many of your Bhopal photos are black and white. How do you see the difference between black and white and color photography? Is that always a conscious choice?

PB: Black and white is beautiful – but it lost its commercial applicability within the media after the mid-80s. Then everything went color. For many years, even Time magazine in the 80s published black and white, until they went color. It’s kind of sad that you couldn’t shoot black and white. On the other hand, to be able to masterfully handle color is not the easiest thing. Now, with the digital era, it has become much easier.

SAI: What is your process like as a photographer – are you always in the photographer mindset?

PB: I think it’s a natural process of having a recording device with you. Not always is what you do is great – you fail a lot, and it’s the jewels that shine through.

SAI: One of SAI’s Seminar Series tracks is ‘South Asia Without Borders.’ In your work, how do you see borders in South Asia, and also as someone whose heritage represents many countries in South Asia?

PB: That is something I’m working on – I’m starting in Burma, and I plan to work over the next 5 years all over the region. I will work in Bangladesh, Pakistan, in India, all to connect the family thread.

This interview has been edited lightly for clarity and length.

-Meghan Smith